English Department Relaxes Guidelines Around Required Books

Creek’s English teachers give their opinion on curriculum changes

Many teachers are supportive of the curriculum change. “I really feel like I have to love the books that I read. I’m in this because I’m passionate about literature,” Morris said, “I’m passionate about students’ learning and I want students to also like literature and not be turned off by the time they’re done with my class.”

February 25, 2022

The Cherry Creek English Department got what teachers are calling “a facelift” after English Department Coordinator Kim Gilbert relaxed guidelines around required books across grade levels.

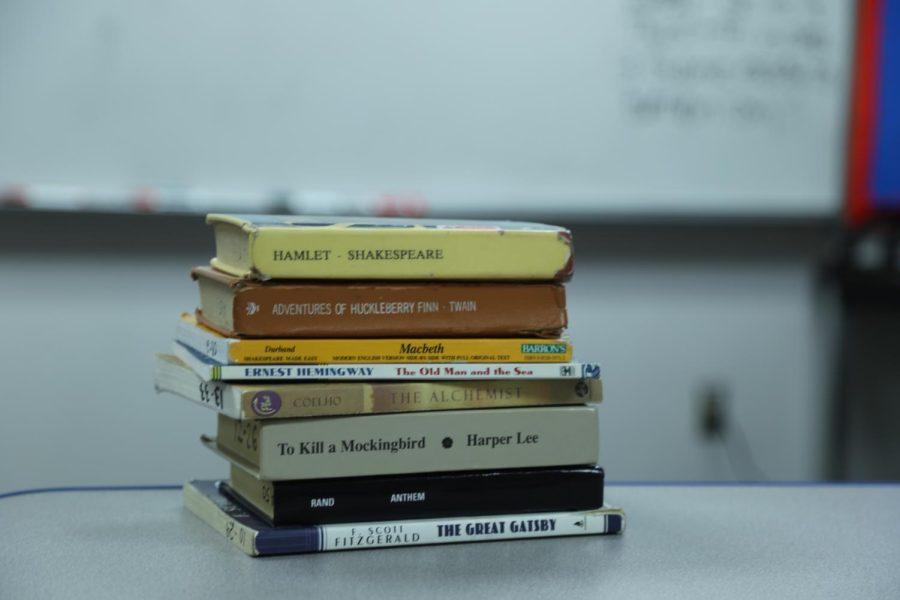

Historically, each grade level was required to read a certain text. Teachers say one of the benefits of required reading is cultural capital and well refined units, but the drawbacks are outdated texts that can become boring to teach over time.

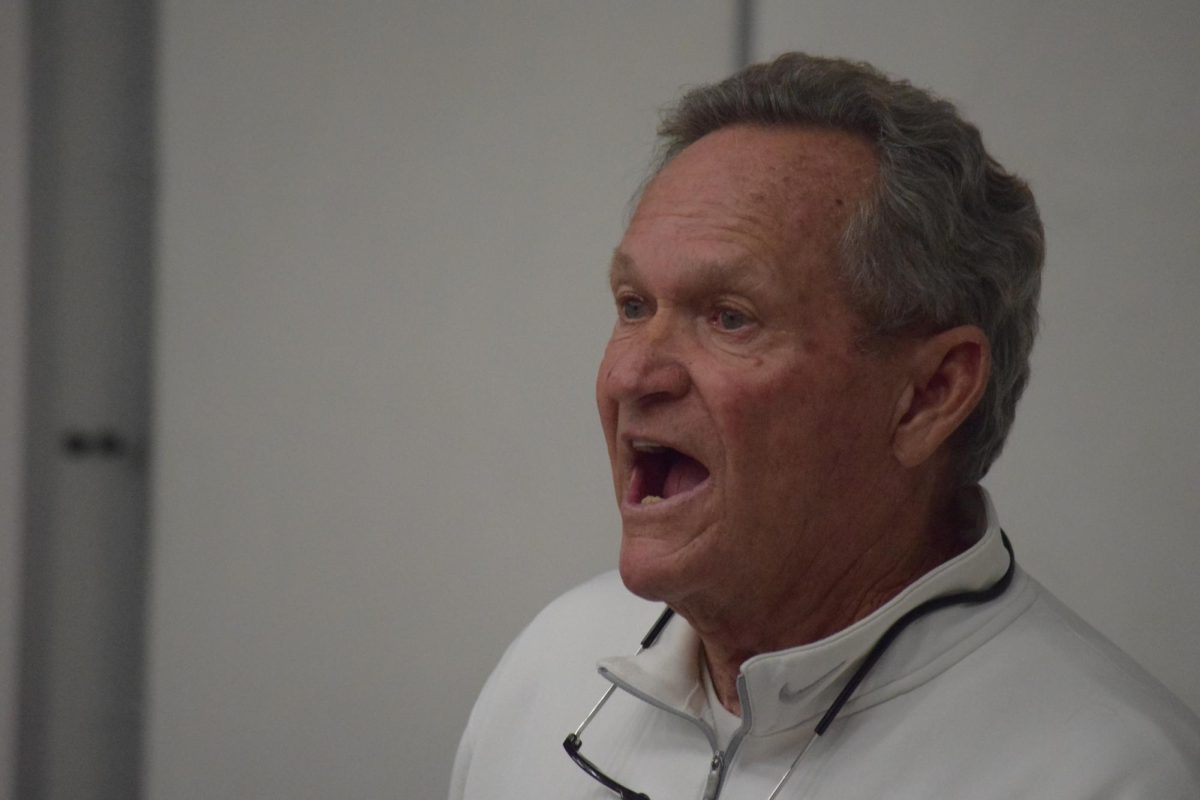

“I think that many years ago, teachers would probably say, ‘Well, we think our students need to have this core base of knowledge, every student should read these certain texts, and it should be part of their cultural knowledge for when we send them out to college or into the world,” English teacher Joel Morris said.

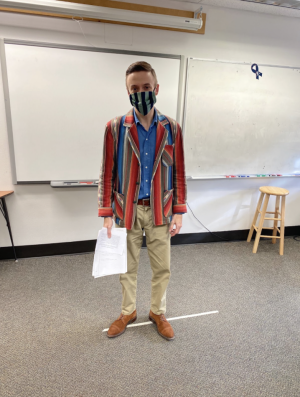

The shift in thinking came with the reevaluation of what skills the department needed to teach in order to send students into the world after high school. English teacher Andy Eichorn realized he didn’t need to teach the book, he needed to teach units.

“One of the things, for example, we try and instruct ninth graders to do is how to elegantly blend quotes into their writing,” Eichorn said, “I can do that with any title, so from a skill standpoint, the title becomes the vehicle for our goal.”

Another reason for relaxing the guidelines was giving teachers an opportunity to not get stuck in a rut teaching the same books year after year.

“I really feel like I have to love the books that I read. I’m in this because I’m passionate about literature,” Morris said, “I’m passionate about students’ learning and I want students to also like literature and not be turned off by the time they’re done with my class. Sometimes you get tired of teaching the same thing year after year and you’re like, ‘you know, I’ve done this book enough, I want to try something new.’”

English teacher Emily Cave said that she also likes to bring in new titles to spice things up. According to her, it’s also fun for students to have new things to read because it fosters more creativity and love for reading.

“[New books] require me as a teacher to be more inventive with what I’m doing and to change things,” Cave said. “It’s really nice to give some more choices in terms of how we’re teaching certain aspects of different skills, and so I don’t necessarily have to teach the exact same books as the teacher next to me as long as the skills are the same. So I think it just creates more creativity for teachers, but it also creates more creativity for students too.”

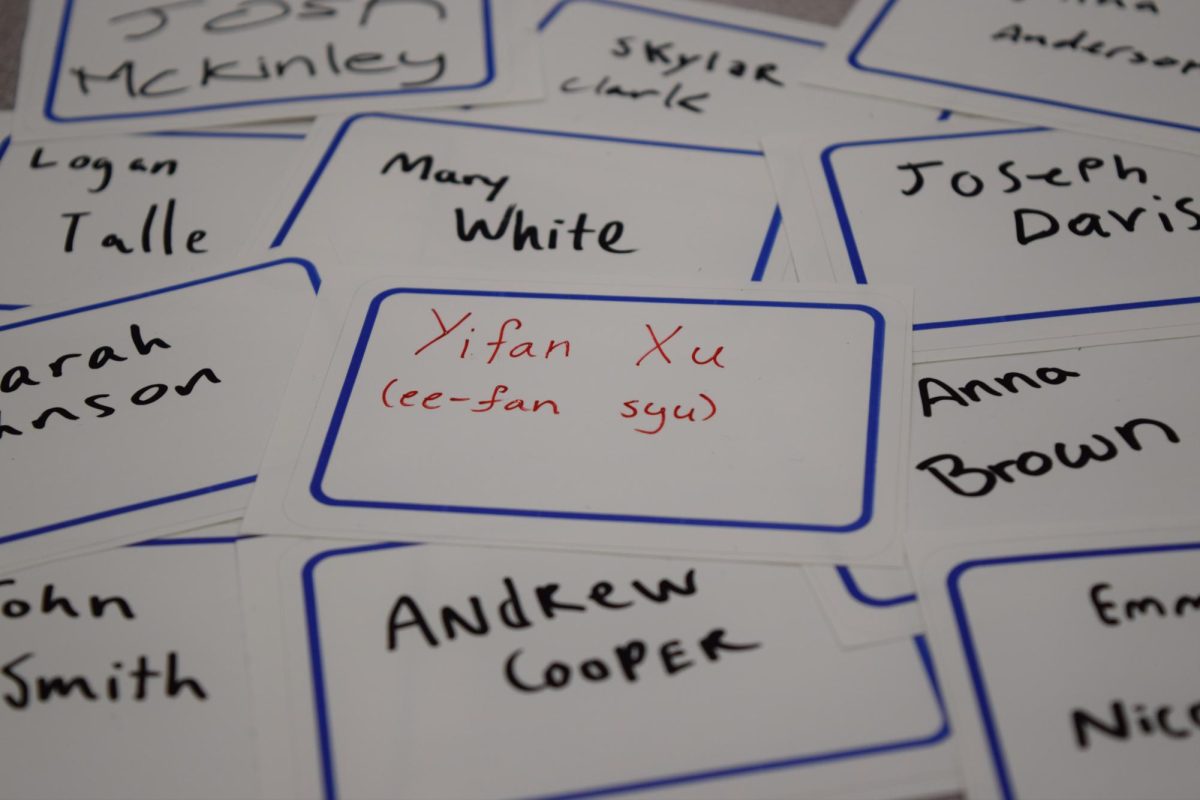

Teachers were also interested in bringing more contemporary titles into the program that were more representative of the student body.

“I think there were a number of teachers who were questioning relevance in our department and the students in front of us versus the students that used to be in front of the teachers before us,” Cave said.

As teachers looked to make moves forward, Eichorn also raised the point that he doesn’t think a title should be thrown out just because it has some components that could be viewed as politically incorrect, because it offers a lense into the past and a chance to experience how people lived in the time that it was written.

“I think when we look at a novel like To Kill a Mockingbird, it’s easy to say here we are in 2022 and this thing in this book is unacceptable in today’s day and age, but I think the other way to look at it is not to bring the novel forward, but to look at us as time travelers backwards, and to go into that world,” Eichorn said. “To be able to say ‘okay this is the way people thought back then,’ and we can use that as an opportunity to tear down some stereotypes perhaps, but also as a means to say’ okay, looking back on it, this scene in this book, is not a good message,’ but look at what is good in this book that this author has done. I don’t think that we should completely dismiss old content and old subjects based on one scene in one chapter or something like that when the totality of the good maybe outweighs the bad.”

Eichorn continued to say that he is proud of how the department has made strides toward inclusivity, and that he is still going to teach some of the books that he taught before the relaxed guidelines because he has spent decades perfecting units for his students.

“We have a number of teachers who are really focused on giving the curriculum a facelift by bringing in new titles with better representation in terms of women, minority characters, and even some of the social issues, which I think is wonderful, and I’m very inspired to take a look at those things. But one of the one of the things about being a teacher that you learn is that there’s a difference between reading a book and preparing a unit for students,” Eichorn said. “It takes a long time to put that together and I think that some of the titles that I’m still holding on to aren’t so much because of the titles, but it’s because of the units I’ve constructed. I’ve had decades to tweak these things and refine these things, and there’s something to be said about having resources that have been developed over the course of many, many years.”

![In a recent surge of antisemitism nationally, many have pointed towards social media and pop culture as a source of hate. “Many far-right people have gone on [X] and started just blasting all their beliefs," Sophomore Scott Weiner said.](https://unionstreetjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/antisemitism-popculture-2-1200x675.jpg)