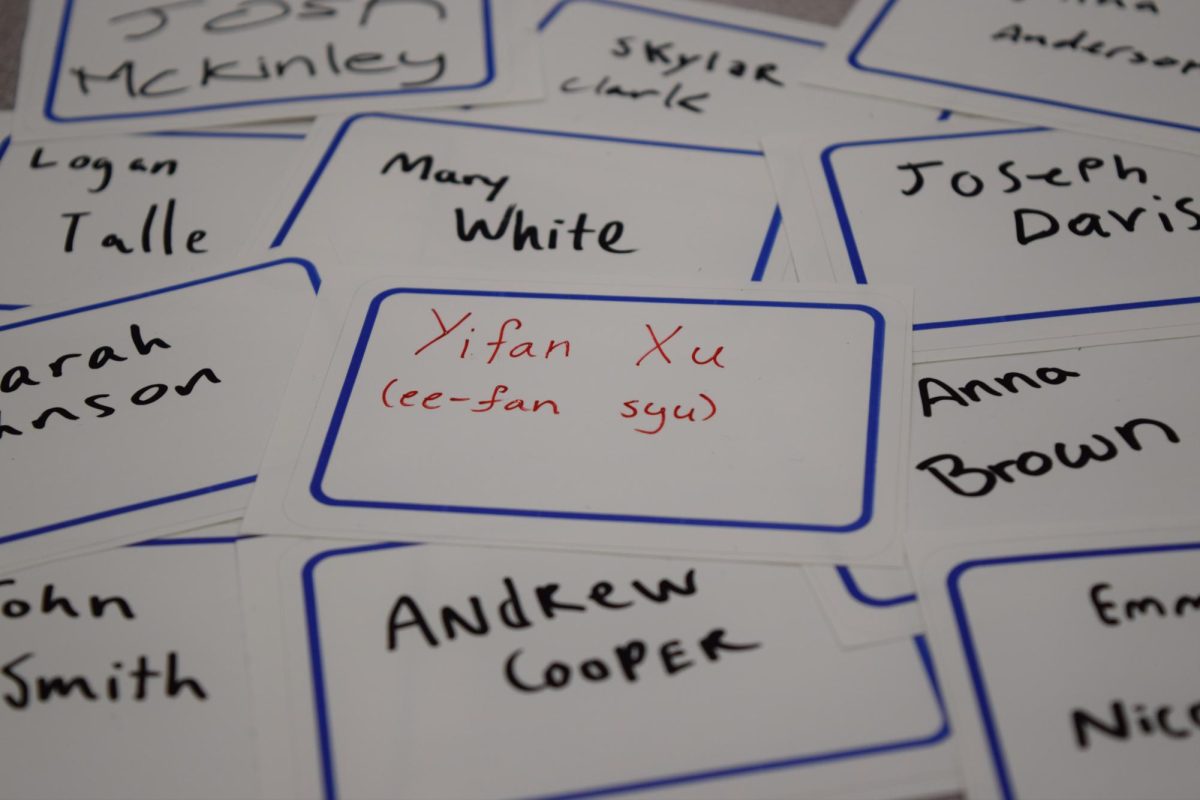

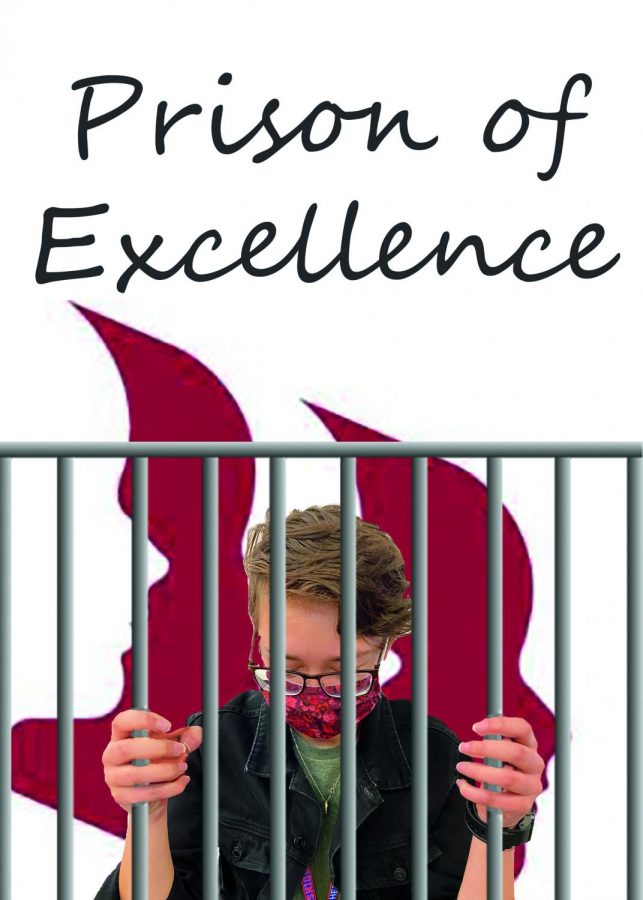

Prison of Excellence

Students feel locked behind the bars of pressure, excellence, and elitism, and it takes an immense toll on their mental health

We have to be the best at everything, and when that doesn’t work for us, we start to fail because we’re just under so much stress,” junior Lorcán Boyd said.

March 25, 2021

The Cherry Creek School District is “Dedicated to Excellence,” but for many Creek students, achieving that excellence means giving up big parts of themselves, most often their social lives and happiness.

Science teacher Lauren Sutton teaches all honors classes, and she sees these problems – and their consequences – firsthand.

“They’re very committed to getting high grades and doing very well and pushing themselves,” Sutton said. “But they will do that at a high cost to their mental health. A lot of times they end up staying up very late, working very hard, pushing themselves, and just in general feeling a lot of pressure to succeed.”

Students give up things like their sleep because they feel it is worth getting a higher grade, but it still does not always work out.

“On a certain day, they might come into class looking quite down,” Sutton said. “If they got a test score that they weren’t happy with, or they feel like isn’t representative of their best work, then they come in and they’re upset.”

Sutton likes to see students challenge themselves by taking an honors class. Even if they do not receive the grade they hoped for, she views it as better than a student taking an easier route for the sole purpose of getting a very high grade.

“They’re challenging themselves, perhaps not getting an A, but working really hard and learning a lot of material,” Sutton said. “But people don’t really like to see that happen, they want the high grade.”

Students argue that the grade is more important than the knowledge because, at the end of the day, a grade is what goes on your high school transcript, not necessarily an accurate evaluation of your knowledge.

“Our system is based around grades,” sophomore Giselle Marians said. “You have to take an AP class at some point in order to get into a good college and for people to think that you’re smart.”

Junior Lorcán Boyd also feels the pressure around getting good grades, and he says it has a huge impact on how he views himself.

“When our grade drops because we can’t handle so much going on in our lives, we feel this pressure to be all-star students, because Creek is “dedicated to excellence” and the top school,” Boyd said. “We have to be the best at everything, and when that doesn’t work for us, we start to fail because we’re just under so much stress. It makes us feel bad about ourselves; we feel like we’re not living up to the standard that we’ve been told we need to live up to for our whole lives.”

Outside expectations of high performance, coupled with societal views of what makes someone intelligent, cause students to feel trapped.

“I don’t have to be taking the advanced classes to be myself, like so many people have told us,” Boyd said. “It’s really more about the grades than learning.”

When students overload themselves with advanced classes, they try to cram multiple hours of work and information into very small time periods. Boyd and Marians agree that the way they deal with this is something that takes away from their learning: memorization.

“I think school is mostly about memorizing because the only stuff I remember is when I’m actually preparing for a test,” Marians said. “Maybe one or two units later, I’ve already forgotten everything from the past test, and I don’t really retain any information from any of it.”

Boyd says that passing is always the main concern, and learning plays second fiddle to how well a student can utilize their memorization skills.

“When we are doing our homework, and when we’re studying, we don’t think ‘Oh I want to be learning this, I want to be educated.’ It’s just, ‘I have to do this because I have to get a good grade on the test.’ So, it isn’t necessarily learning, it’s using [the information] for the moment just to pass.”

Students feel this immense pressure to succeed, and in many cases it is because of one common reason – they feel like they must take all advanced classes to get into an elite college. Many educators and mental health professionals at Creek have had discussions about where this pressure comes from because they are concerned that it is not good for students’ mental health and learning.

“It probably comes from pressure at home, it comes from pressure from society,” Sutton said. “They’ve been told all their lives that they need to perform, and they need to go to these great schools, and they need to get scholarships to do it.”

Sutton says that because of this, kids sometimes push themselves over their limits because they do not want to be a disappointment.

“I have said to them, that if you decide to drop down to CP biology next year as sophomores, you are still going to get an excellent education,” Sutton said. “But I still feel like a lot of them think that is a step down in some sense, or they’re going to be letting someone down, letting themselves down, or they’re not going to be living up to this stigma of ‘I’m smart, I need to be in high level classes.’”

Students agree that there is a huge stigma at Creek around taking advanced classes, and going to a top tier college.

“We are told that in order to be successful in life, we have to graduate from Creek with flying colors and get into the best college,” Boyd said. “And then when we get into the best college, for all four years we take the hard classes and end up with better paying jobs. I feel like most kids are told that’s the only path.”

Boyd sees the danger in students only thinking they have one path: If this notion of an elite college being the only option is why students push themselves so hard, because the other option is absolute failure, and there is no in-between.

“I do feel like students should have the desire to get good grades,” Boyd said. “But Creek pushes it too hard on us that that’s what we have to do to succeed in life. And if we don’t, then we’re going to end up homeless on the side of the street.”

The advantages of going to a community college, such as incurring less student loan debt, get overshadowed by incorrect beliefs that people who attend community colleges are less intelligent.

“[People think that] if you go to a community college, that’s bad and you’re not smart, and you probably don’t have enough money to go to a better school,” Marians said. “ It wouldn’t be very good to go there because everyone would look down on you.”

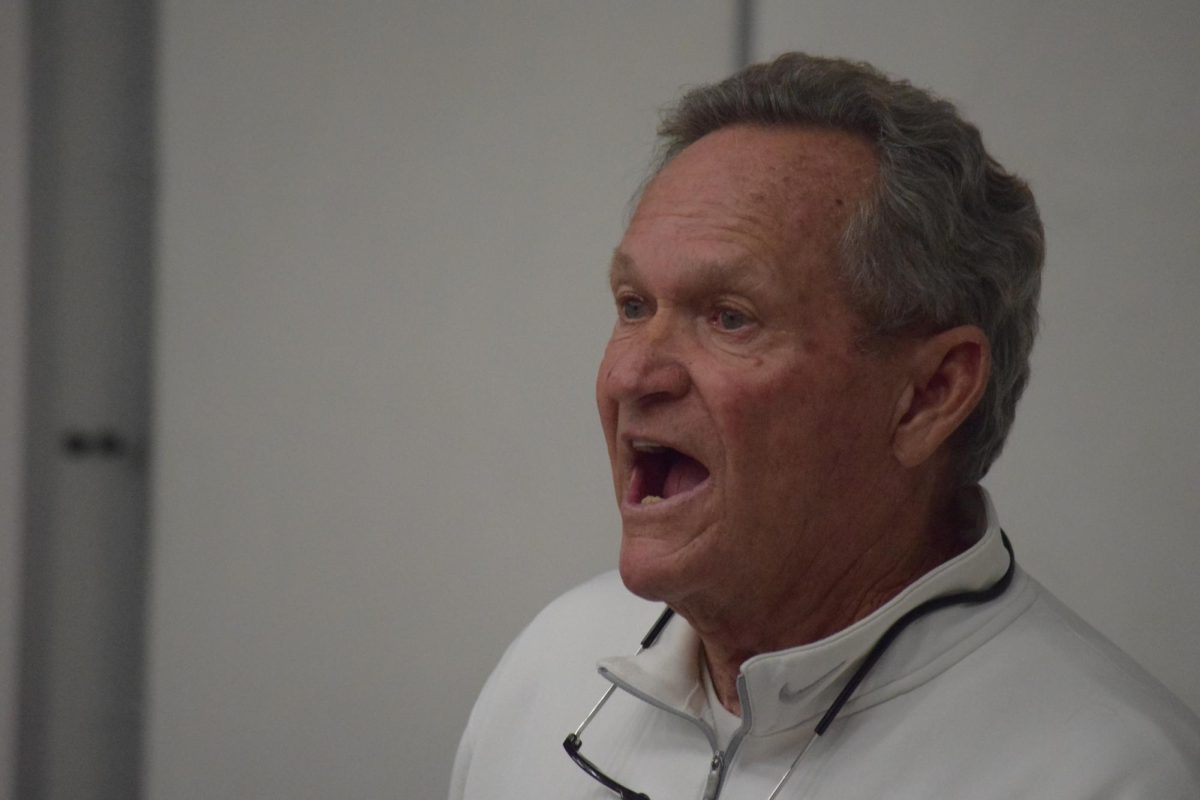

According to Post Grad Coordinator Craig Wittgrove, who came to Colorado from California, elitistism is not exclusive to Creek; it’s a problem in Colorado as a whole, especially in high performing schools.

“I do think there is a misperception of the advantages of a community college and what they can provide,” Wittgrove said.

Other states with bigger populations have different views of community colleges.

“In California, the community college system is something that is very valued because there’s only so many spots in the University of California system [or] at Cal State, and there’s way too many people. There has to be another funnel to help them get to that program. For whatever reason, whether it’s financial, whether it’s you want to be closer to home, whether it’s academic – maybe you weren’t quite the student you needed to be to be admitted into this [highly selective] institution

Wittgrove wants people like Boyd – and all Creek students – to realize there are far more paths to success than just the most highly selective colleges.

“Paying $70,000 a year for four years, there’s not too many people who can just write a check like that. The community college system offers a great pipeline that we do need to be considering more often for sure,” Whitgrove said. “One of the founders of Costco went to San Diego State, and not everybody knows that. They think that all those people all went to Ivy Leagues, and so it’s about helping to educate them that there are those different paths.”

Wittgrove says that today, colleges are concerned more about their students’ mental health because they are seeing more problems arise on their campuses. Part of Wittgrove’s job is to communicate with colleges about why these things are happening and work to solve problems.

“They might not have seen that as much before, and now they are, so now it’s something that’s relevant for them. They’re coming back to us and asking why is this happening, and what can we do? We’re sharing with them, when it takes 20 AP classes to get admitted to your institution, that’s why they’re doing it, because they feel, and they think, that the only way I can be admitted to your highly selective institution is by this route.”

Colleges’ concerns about mental health have opened lines of communication between high school administrations and colleges about mental health, and changing admissions requirements.

“The dialogue and the conversations are happening more than they’ve ever had,” Wittgrove said. “It makes me optimistic that things might shift.”

Despite these efforts, most students still believe going to an elite college makes you better in some way than someone attending a community college. Students are striving to be the kid who gets into a prestigious university, and the nation is seeing a huge rise in mental health issues as a result.

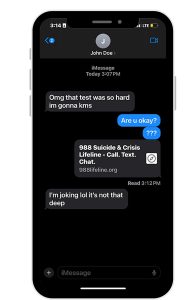

“This is reflective of national data that we have had access to since at least 2005,” school psychologist Andrew Russell said. “We’ve seen pretty sharp upticks in what we’d call internalizing mental health disorder. That would be things like anxiety and depression, the things that aren’t directly observable.”

Russell says these internalizing disorders are in large part due to something called chronic stress.

“When you’re never not stressed, and you’re perpetually in the system of chronic stress, that’s bad,” Russell said. “Everything falls out of balance; there’s physical health, things like weight gain and sleep loss that happen, and also these downstream mental health effects. I don’t think it’s a Creek issue, but a high-performing school issue.”

Boyd explains how chronic stress and the pressure to perform affect him personally. While these stressors might not be unique to Creek, they impact kids significantly as they get older and start taking more advanced classes.

“I feel the stress building up as I get closer to college,” Boyd said. “With all this work and this pressure to keep being the best and getting the best grades, it just keeps adding and piling on. The lack of being able to go out and have fun, it’s just been horrible on my depression. Then with my anxiety, with the work and all the other stuff going on in my life, including my job, there’s so much that I need to think about, and there’s so much that I need to be doing. It’s so overwhelming and makes me so anxious.”

Boyd feels like he does not get the chance to be a kid because his time goes primarily toward school.

“The biggest sacrifice I make would be my social life,” Boyd said. “I’m sure it’s the same way with a lot of people, just because we do have chores and stuff we need to do at home, plus the homework. It gives us not a lot of time to go out and be with friends, doing things that excite us and get us happy.”

Boyd said if he had more time, he would spend it with his friends, because he wants to add more happiness into his life.

“Just going out with friends more, getting out to see one or two more people during the week, would be such an improvement,” Boyd said. “The social aspect is what fuels our joy, so getting more time to be out with people, and to be outside doing things instead of just inside looking at my computer, that would be incredibly beneficial.”

Marians also said that when she has free time, such as over summer break, she can go outside and have fun.

“During break my mental health is so much better,” Marians said. “I don’t feel like I have so many things to do, I can just relax and really do what I want without stressing about what other people want me to do, and all the homework assignments and studying and doing well on tests. I can just relax, maybe go outside and spend all day with my friends, which I can’t do during school.”

However, students are still in school for the majority of the year, and they need mental health systems in place at school that can help them.

“I do think that the administration here cares very deeply about the mental health of its students,” Sutton said. “Does the administration and teachers always make the right choice? No. But it’s very difficult to do what’s best for every single kid when there’s 1000s of kids, because what’s best for every kid is different.”

Sutton thinks that because every kid is unique, the best solution to the problem is for kids to have teachers that they can seek out for help.

“The thing that’s put in place here that’s the most helpful is just the availability of teachers to be there for kids to come in and talk, to seek support,” Sutton said. “That’s going to be what helps kids the most, just being a place for them to come, get a hug if they need it, cry, and just get support.”

One of the biggest consequences of being dedicated to excellence is the loss of a life away from school. As a teacher, Sutton wants to see kids do well in school, but she also wants them to live separately from her classroom.

“Not only do I consider mental health, but another thing I consider with the homework I give is extracurricular activities,” Sutton said. “I want students to be involved in things outside of my classroom. The more involved students are, I think the more they succeed, not the less they succeed. I want to honor the fact that I would hope that they are involved outside of school, and give them time to do that.”

Sometimes, there is just not enough time in the day to do work for all of their classes, do household chores, and do things that make them happy, which is why students are constantly battling to choose.

“We feel buried underneath so much stress and so much work,” Boyd said. “We are drowning in it.”

This story won honorable mention In-Depth News Coverage from CSMA.

![In a recent surge of antisemitism nationally, many have pointed towards social media and pop culture as a source of hate. “Many far-right people have gone on [X] and started just blasting all their beliefs," Sophomore Scott Weiner said.](https://unionstreetjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/antisemitism-popculture-2-1200x675.jpg)