(How) Should We Teach Race?

How the Critical Race Theory debate reached CCSD

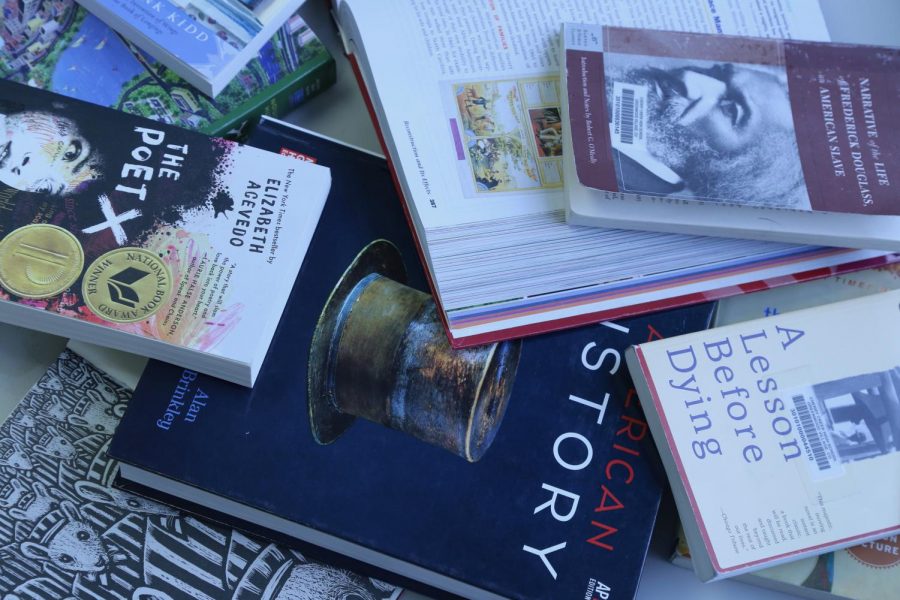

Books and literature often provide deeper context for historical knowledge. At Creek, many teachers choose to teach books that introduce difficult discussions about race in American history.

October 25, 2021

The United States has a long, complicated history with race.

For centuries, racially-motivated divisions have sowed hatred, fear, and violence. And as America faces yet another racial reckoning, schools have become the center of complex debates about how we discuss race.

You may have heard of critical race theory, a method of studying history that considers how institutions, like the law and the economy, have created systemic inequality. Critical race theory, or CRT, isn’t that new – it was created in the 1980s as a grad-school level way of thinking and learning, according to a New York Times article by Jacey Fortin. But it’s become a widespread center of controversy more recently.

For teachers, this has sometimes been difficult.

Dr. Jennifer Koshatka Seman, who teaches American and Latin American history at Metropolitan State University of Denver, as well as graduate courses for K-12 teachers who want to expand their expertise in social studies, said that for many teachers, controversies surrounding curriculum have made it harder to teach.

“This depends, of course, on which state you’re in,” Seman said, “and what school district and the kind of backlash you get. Obviously, in places like Texas, Oklahoma, some teachers are rightfully scared.”

Some Creek teachers, especially in the English and social studies departments, have often used pieces of literature, depending on the class, to introduce difficult conversations about race. But because of these more recent controversies, this has become more difficult for some teachers.

“I used to, but I won’t anymore,” one English teacher, who preferred to remain anonymous, said of teaching race in their curriculum. “I’ve had a parent question my entire curriculum before, so once this controversy started, I opted to stay out of conversations involving race as much as possible. This is disappointing because I feel like our classes can be safe spaces for students to explore their thoughts and feelings about difficult topics as they navigate their way to adulthood.”

But part of the problem with the critical race theory debate is the general misunderstanding, from all sides, of what CRT actually is.

“I think there is a huge difference in teaching kids ‘Critical Race Theory’ and ‘understanding the world around us,’ and unfortunately the two are getting confused,” English teacher Jenna Chapman said. “Exposing ourselves to others and their lived experiences allows us to understand perspectives other than our own. This exercise helps us develop as empathetic people and allows us to better connect as humans.”

English teacher Emily Cave had something similar to say. “I would say that the misinformation about what Critical Race Theory is and is not creates a unique challenge for teachers who have been working for years before this terminology came into focus to broaden the scope of the voices that are heard,” Cave said. “Critical Race Theory is a very complex way of looking at content that is, quite honestly, beyond the scope of understanding which would benefit the average student. Including a variety of perspectives that create access points to the content of the class for more students is a vastly different thing than teaching Critical Race Theory.”

Social studies teacher Fletcher Woolsey said that CRT has been misinterpreted on both sides. “People who are in favor of the theory can make the mistake of over-applying it or treating it as a concrete fact,” Woolsey said. “This idea that much of American history is guided by or directed by sort of racist undercurrents certainly is a possibility, but it’s almost impossible to empirically prove that. On the other side of the problem, it gets misinterpreted that critical race theory is basically blaming white people for everything, and anything bad that has happened has happened because of selfish, racist, white people.”

According to Woolsey, much of the pushback against CRT is due to these misunderstandings.

“That’s where you see a lot of the pushback from white parents that we see active today, is this sense that ‘my white kid is going to go to school and be told constantly, only how terrible he is because of his racial groups,’” Woolsey said. “That’s the fear. And that isn’t what it is.”

The History

The debate around teaching race history has been going on longer than you might think, although it hasn’t always taken the same name. In fact, almost directly after the Civil War ended, there were already conflicts over how to teach race in schools. Immediately, there were people, primarily in the South, who tried to cover up some of the atrocities that had occurred.

“After the Civil War was fought, and slavery was overturned legally, there was this period of Reconstruction,” Dr. Seman said. She reports that “in the South, those that were resentful of that, and those that thought that the war was unjust and their society was ‘taken’ from them, began to promote this alternative idea of the past, this ‘Lost Cause’ mythology.”

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy, or just Lost Cause, refers to a widely spread myth that the Confederacy’s motivations were heroic and not simply centered around slavery. Tracy Thompson, writing for Salon, calls the Lost Cause ideology “a vigorous, sustained effort by Southerners to literally rewrite history.”

The narrative was pushed by organizations such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which is an organization founded by women descendants of Confederates. The UDC fought to paint a pretty picture of the Confederacy by writing textbooks, sponsoring historical museums, and building monuments – many of which have become the recent center of controversy and protest – among other things, all meant to create a positive image of the Confederacy and a romantic view of plantation life.

“Going back to the daughters of the Confederacy and the kind of alternative textbooks and alternative histories they put out about the Civil War, it’s basically just a rewriting of history,” Seman said. “So it’s basically a whitewashing and sometimes just literal fabrications. If you ever look at any of those textbooks, it’s just outrageous the things that become enshrined for those folks that read that. And that becomes the truth because it’s in a textbook and ‘it’s what my elders tell me.’”

The main problem with this narrative, and the subsequent propaganda surrounding it, is how intentionally misleading it is. Often, you will hear the argument that the Civil War was instigated over states’ rights. But, according to most historians, when it comes down to it, every other motivating factor in the Civil War boils down to one thing: slavery.

Thompson describes it like this: even as the South claimed its motivations were financial or a matter of states’ rights, “there was never any doubt that the billions of dollars in property represented by the South’s roughly four million slaves was somehow at the root of everything.” But despite this, the UDC and other related organizations were often successful in re-painting history and reframing the Confederacy.

The problem began there, with a division of how history was taught depending on who wrote your textbooks.

Blatant racism in textbooks, in fact, continued on for decades. In the 1900s, this language could be found in textbooks even outside of the South.

Woodrow Wilson – historian and future president – wrote a textbook, “A History of the American People,” in which he described Black Americans’ “ignorance and credulity,” which Wilson suggested “made them easy dupes” during the Reconstruction era as Northerners came to promote economic development in the South. According to Wilson, these white people were “carpetbaggers,” visitors to the South who were there to take advantage of formerly enslaved people, who, according to Wilson’s racist narrative, were easy to confuse.

Whereas Wilson dismissed the intelligence of formerly enslaved people, he was more generous to their persecutors. He described the Ku Klux Klan as a “secret club for the mere pleasure of association” founded by men who wished “to rid themselves…of the intolerable burden of governments sustained by the votes of ignorant negroes.” Wilson claimed that the Klan’s campaign of intimidation and violence came about “almost by accident.”

Wilson was from Virginia, a Southern state, but this kind of narrative was present all over the country.

Thomas Bailey’s 1966 “The American Pageant,” which is still used in public schools today (in revised editions), describes the granting of basic rights to formerly enslaved Black Americans as a “stark tragedy,” saying that while “wholesale liberation was probably unavoidable,” the granting of “wholesale suffrage” was “both selfish and idealistic” on the part of Northern whites.

He adds that “the bewildered Negroes were poorly prepared for their new responsibilities as citizens and voters.”

While Bailey was more critical than Wilson of the Ku Klux Klan’s violence, he still described Klan members as “once-decent Southern whites” who were “goaded to desperation” by the supposed tragedy of Reconstruction.

It’s very easy to see how this language is problematic.

And, as one New York Times report by Dana Goldstein found, textbook problems are still apparent today, even though textbooks now are unlikely to blatantly excuse the KKK.

She compared American history textbooks from California and Texas, and the results were striking – but not necessarily surprising. Much of the language used in the California versions of textbooks about not just race, but gender, sexuality, income, and other forms of historical inequality is completely missing from the Texas versions of the same exact books.

One example Goldstein lays out is from a section about the Harlem Renaissance, a 1920s movement of Black art, literature, and scholarship. Whereas California students learn not only its effect on Black culture, but also of the backlash it received, Texas students read this sentence of why white people were resistant to the Harlem Renaissance: “Some…dismissed the quality of literature produced during the period.” This excerpt is an example of how the Lost Cause narrative persists even today.

More recently, there have been movements to correct widespread myths about race, the Civil War, and Reconstruction.

One prominent example of this is the 1619 Project, a set of articles and artistic pieces featured by the New York Times that is meant to be used when teaching slavery to students.

The 1619 Project was published on the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in North America. Taken together, the articles featured in this collection show how slavery lay at the very core of American history rather than on its periphery. They argue that we can’t truly understand American history without understanding slavery.

Seman says that the 1619 Project served as a focal point for the debate around CRT.

“[The 1619 Project] was obviously very successful among K-12 educators,” Seman said. “The Trump administration very, very openly took a stance against what now everyone’s lumping together as critical race theory, coming out of The 1619 Project.”

In response to the 1619 Project, Trump called an advisory board that he called the 1776 Commission. The dates are symbolic; 1619 asks us to consider slavery as the focal point of American history, whereas 1776 focuses our attention on the Revolutionary War, when Americans were supposedly united in a patriotic cause.

The 1776 Commission lauded the idea of “patriotic education” in which history classes concentrate on American achievements and ideals rather than the nation’s more complicated and uncomfortable history. Trump discussed this commission and patriotic education during his Republican National Convention speech in August 2020.

Out of the clash between CRT and patriotic education came what we have now. And much of this debate has been from vocal parents who are concerned about what their children are being taught.

The Parents

One CCSD parent, Schumé Navarro, who is currently running for the school board, described how she thinks CRT is, or has the potential to, “ruin kids.” She raised the concern that CRT and similar teaching methods are teaching children to see people by the color of their skin.

“It’s [CRT] creating these environments where…a relationship could happen, where you could work together, where you could find your new best friend, your new partner…and we just aren’t allowing that to happen because we’re so concerned with skin color,” Navarro said. “I think it’s creating the most racist environment I’ve ever seen. And that’s how I feel like it’s ruining [kids].”

Navarro described examples she’s seen of this, from a family member who wasn’t willing to interact with white people to a neighborhood kid who thought another boy had hit her because she was Black.

According to Navarro, some of what kids are being taught in elementary school was their own biases and privileges. She described examples of young students being asked to make a list of their own personal privileges. “We have a fifth grader who was told to write down his privileges and say his race,” she said. “He’s 10, he shouldn’t have to be in that space.”

Navarro believes that the 2020 murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police and the subsequent Black Lives Matter Protests are the main factors behind the bloom of the CRT debate, including in CCSD. Legislation was recently passed in Colorado to include more conversations about race in elementary social studies curriculum. Navarro said many of the guidelines laid out in this curriculum risk alienating white students. Other parents disagree.

CCSD parent and former Creek PTCO President Andrea Davoll said that what’s at stake here isn’t CRT at all, but rather an accurate depiction of history in schools.

“We don’t really teach that [CRT] in Cherry Creek Schools anyway,” she said. “We try to portray history as honestly and clearly as we can. And we try to talk about race in ways that honor and respect all cultures.”

Davoll said some parents were worried about the new curriculum, but that CRT isn’t really a factor in the district.

“What appeared to set off some of this was the introduction of a new social studies curriculum, K-5,” Davoll said. “The board voted to approve that social studies curriculum, after an extensive and transparent process, including all stakeholders, to select a new social studies curriculum that was just more culturally responsive. A lot of parents, I think, falsely equivocated that with critical race theory, and became very upset.”

School board president and parent of Creek graduates Karen Fisher said that the new curriculum is vital in making minority students feel more heard and understood.

“In Cherry Creek Schools, it’s not just about cramming for the test, or getting an ACT score, it’s also about feeling heard and included and connecting with staff,” Fisher said. For that reason, “it’s crucial to have culturally relevant, accurate history.”

Davoll talked about how learning accurate history is important, and how, after the murder of Floyd last year, she found it important to discuss the issue with her kids. She explained how they balanced their family’s history of law enforcement with the sadness they felt after the murder.

“My father-in-law, my kids’ grandfather, was a Denver police officer,” Davoll said. “We really see and grieve for both sides. It should go without saying that too many young people – well, they’re not just young people, too many people are being shot. We are very pro-law enforcement, but we are also very pro-reform. And those two things can coexist.”

Fisher said that she often feels that parents who have spoken out against the recent curriculum change in CCSD seemed “misinformed” and that they didn’t give much concrete reasoning behind their stances.

When the district was deciding whether or not to pass the new social studies curriculum, several parents came to speak at board meetings to express their concerns about the curriculum. The problem, according to Fisher, was that those parents “didn’t give us any reason.”

“I think that many of them probably were driven by politics,” Fisher said. “I think that some of the people who came didn’t have anything specific about Cherry Creek Schools, but were just sort of angry about how divisive everybody [was].”

One organization present at those meetings was No Left Turn, which was created to oppose education “becoming tainted with historical revisionism, political correctness, and the outright rejection of values which have long been at the core of the American experience,” according to their website.

The problem with this, though, was that some of the parents who came from No Left Turn weren’t actually CCSD parents, Fisher said, making it difficult for them to argue for or against issues in the district.

Nonetheless, CCSD’s curriculum change served as a microcosm of the CRT debate, and the way parents have become so involved in it.

So why have parents become so ingrained in the CRT debate?

“I think it’s that they’ve been targeted,” Seman said. “I’ve had some conversations with people [and] they’re like, ‘What is this thing? Critical race theory? It sounds so scary,’ but it’s really not. It’s just honestly assessing where we’re at in this nation. But I think [some are] purposefully targeting parents, and it spreads. You know, people talk.”

The Students

When it comes down to it, though, students are the ones who will learn CRT or not and take that knowledge with them into the future, regardless of what happens. So are Creek kids for or against CRT?

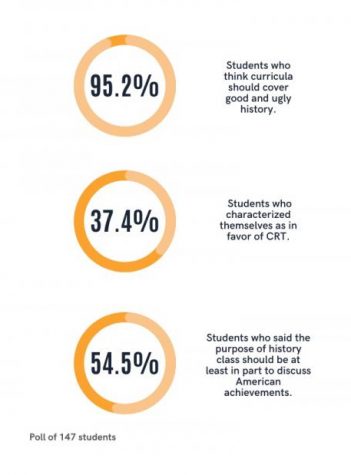

From a poll of 147 Creek students, the answers were fairly split. 37.4% said they hadn’t heard of CRT at all. Another 37.4% said they were in favor of CRT, while 10.9% said they were against it. And many Creek kids have a lot to say when asked about this issue.

“Bias is present in everything humanity does, but that doesn’t mean it has to be pervasive,” senior Kalisi Loveridge said. She characterized herself as in favor of critical race theory. “History has many different sides and perspectives; we should do our best to learn about them all. By teaching more comprehensive content concerning past events, schools can better prepare future citizens to understand and participate in current events.”

Other students noted how politics had become intrinsic to this issue.

“We really need to stop the politics,” sophomore Andy Hsing said. “We already had Trump, Biden, Twitter, and the capitol insurgency; we don’t need this ever again at all.”

A fairly low percentage of Creek students said they were against critical race theory, but few chose to answer why.

“Let’s not teach kids what political opinions to believe but instead let them figure it out themselves,” one anonymous student* who characterized themselves as against CRT said.

There isn’t a lot of data out there on what students have to say about critical race theory. Instead, polls of parents and their opinions have usually been at the forefront of the CRT debate. But of the 147 students polled, 86.3% said students should at least sometimes have a say in what’s taught in school curricula. When adults are in charge of deciding what students learn, kids’ voices aren’t always heard, some students say.

“[Students] should have control in terms of making sure what is taught is true, secular, and appropriate for the age level,” sophomore Toby Shu said.

Shu also cited some real-world examples of where CRT laws – made by adults – have caused issues, saying that “the ban of teaching [CRT] by laws is overbroad and ridiculous.”

“Critical race theory bills in conservative states, like the one in Tennessee, ban ‘division between, or resentment of, a race, sex, religion, creed, nonviolent political affiliation, social class, or class of people,’” Shu said. “Banning of a division between religion or creed would ban denigrating the KKK or Nazism. This is clearly overbroad. Even if they could limit it very narrowly [in K-12 schools], that doesn’t justify the banning of it in colleges, because college students should be able to discuss and learn theories without being indoctrinated.”

Shu continued, noting why, despite gradual social change, learning about racial inequity is still very important for students today. “To say that racial equality hasn’t gotten better would be a lie, but it would also be a lie to say that racial equality has been reached,” Shu said.

No matter what students thought about CRT, the consensus on what we should be taught was clear. With a 95.2% consensus, Creek kids overwhelmingly said they thought students should be taught the whole historical narrative, even – and perhaps especially – the parts that aren’t easy to hear.

“If the purpose of history class is to ‘celebrate American achievements,’ then we aren’t helping students gain a better understanding of anything – we’re feeding them propaganda,” sophomore Eleanor Ross said. “The truth is always important, no matter how ugly it is.”

Junior Kayla Robinson agreed. “I think if we choose to leave out certain parts of history in our curriculum that are considered ugly, we are actively choosing ignorance,” Robinson said. “I firmly believe that the ability to turn a blind eye to certain issues because they don’t or didn’t affect you is a privilege. If we put America on a pedestal so we can celebrate it, we refuse to acknowledge the bad.”

Additional contributions made by Lily Deitch and Amanda Castillo-Lopez.

Infographics by Carly Philpott.

This story was a finalist in the Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion category for NSPA.