Sandra Oh’s “The Chair” Pushes All The Right Buttons

I’m the daughter of academics, and here’s how The Chair gets it right

Netflix

Sandra Oh, known for Grey’s Anatomy and Killing Eve, stars in Netflix’s The Chair as Ji-Yoon Kim, the brand new chair of fictional Pembroke University’s English department. As she navigates being the first woman to hold the role, she must also deal with controversies within the department.

August 31, 2021

“It’s not about whether you’re a Nazi. It’s about whether you’re one of those men who, when something like this happens, thinks he can just dust himself off and walk away, without any [expletive] sense of consequence.” – Ji-Yoon Kim, The Chair

My parents are both professors. I was born into academia. This, to be quite frank, sometimes has its drawbacks. Professors are always busy. They’re far too critical of themselves and others; they work tirelessly, often for students who really don’t give a crap. Grading takes hours, nearly every day. There are hundreds of meetings. There are advising responsibilities. There’s the “publish or perish” pressure — if professors don’t do their own research, publish their work, and add something to the field, they won’t be hired or respected anywhere, so add that onto professors’ workload.

The undebatable truth about academia is that there’s far too much to be done, far too little money to go around, and as a result, far too much on professors’ plates.

Teaching is thankless work. And while it can be gratifying, it can also provoke backlash — sometimes warranted, sometimes not.

But this isn’t about academia in general. This is about Netflix’s The Chair, and how it represents both academia and its intersection with social issues – and why students should care.

Sandra Oh, already known for her impressive roles as Dr. Cristina Yang in Grey’s Anatomy and Eve Polastri in Killing Eve, is Dr. Ji-Yoon Kim, the first female chair of the English department at the fictional Pembroke University. As to be expected, that’s met with backlash enough, but when Ji-Yoon’s colleague and almost-love interest Dr. Bill Dobson (Jay Duplass) jokingly heils Hitler in class, sparking a campus-wide furor, she finds herself dealing with even more than she signed up for.

Bill refuses to apologize thoroughly, convinced he didn’t really do anything wrong, and because he did do something wrong, this reaction is obviously inadequate. So then we get into a deeper issue: what is a good apology, and why don’t we get them more often?

The line I put at the top resonated with me very deeply for that reason. Bill argues in the show that he’s not actually a Nazi, and he was just joking, so why should he have to apologize anyway? And Ji-Yoon has the perfect response: we live in an age where people don’t give full apologies. Instead, they apologize for how we’re feeling because of their actions. It happens all the time, from TikTok stars to baseball players. It’s almost victim-blaming. In fact, it is victim-blaming. And it’s considered perfectly acceptable by far too many.

Bill’s Nazi-salute gaffe is a perfect example of warranted backlash. He did the wrong thing, and he refuses to take responsibility, and it makes it hard to sympathize with him. I certainly don’t.

It’s easy, and valid, to get angry at those at the top in cases like this. Ji-Yoon is reluctant to take action, no matter how much she acknowledges that what Bill did is wrong; the administration’s actions are clearly performative, from the inside and out; and Bill is quite literally sitting at home with few concerns about his situation (although he does attempt to draft an apology — it’s a bad one).

And as Bill gets himself suspended for refusing to apologize, the university’s dean replaces him with none other than David Duchovny (a personal favorite of mine — see my love for The X-Files), because administration thinks his name will attract — and calm down — angry students. Duchovny, though a well-educated, well-known author, doesn’t even have his doctorate. It’s a facile, pandering maneuver that fails to acknowledge the real issue at hand and skips over the concerns of both professors and students. (However, Duchovny’s episode is hilarious. He plays himself very well. His lack of understanding of academia is well-represented and possibly my favorite part of the whole show.)

And yet, The Chair doesn’t villainize academia. Because while Bill has majorly screwed up, he’s not the main character. He’s not the only character. And that’s where this show delves deeper into the complexities of academia — the good and bad, the systems versus the people.

Misogyny is an important theme. Misogyny is a stubborn problem in real-life academia, too. My mother — heck, any female professor — can quote real examples of students questioning whether women professors have “actual doctorates” (they do) or just refusing to refer to them as “Doctor” at all (take the recent example of First Lady Dr. Jill Biden, in which some people were convinced that she wasn’t a real doctor). Just this semester, my mom had a student who questioned whether she was an “actual expert” in history (she is). And for those reasons and many others, the importance and accuracy of The Chair’s representation of misogyny in the university workplace skyrockets.

Almost every female character is also experiencing some similar form of misogyny or racism.

Dr. Yaz McKay (Nana Mensah) is a Black, untenured professor in the English department. Aside from Ji-Yoon, she’s the only woman of color in the entire department. And her chances at getting tenure lie mostly in the hands of Dr. Elliot Rentz (Bob Balaban), a fossilized, white, male professor who has fallen severely behind and neglects to update his curriculum. It’s an issue often discussed but rarely dealt with — women, especially women of color, face unfair or unequal standards in academia. In this situation, once the university felt like they were doing something by appointing a woman of color — Ji-Yoon — chair, they felt like they had done enough for the day. This is also reflected in the real-life story of Nikole Hannah Jones – a prominent Black Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalist behind the New York Times’ 1619 Project who was denied tenure at UNC-Chapel Hill, despite her predecessors receiving tenure. Eventually, she left UNC for Howard University, even after UNC agreed to give her tenure.

Have you heard of Rate My Professors, the website where any student can leave a Yelp-like review on their teachers and professors? It’s the worst possible representation of educators. It has been proven that women academics consistently fare worse in these “reviews” than men. This problem is more pronounced in official evaluations, which students fill out anonymously and are used for decisions about tenure and promotion. These are just as likely to reflect bias against women and people of color, but unlike the posts in Rate My Professor, they can have serious consequences for people’s careers. And yet, millions of students every year pick their professors from a catalogue of hypocritical and faulty reviews.

In The Chair, Dr. Joan Hambling (Holland Taylor), an elderly white professor, has been teaching for a long, long time — but now, the university is trying to cut her out. She’s outdated, apparently, and enrollment in her classes is down, so she gets banished to an office under the gym where the Wi-Fi doesn’t even work. The evaluations she’s receiving from students, both official and on Rate My Professors, are negative and biased, and she feels she needs to go so far as to burn the evaluations or hack the website to see who’s leaving them and why. Meanwhile, Dr. Rentz, whose ratings on Rate My Professor are equally negative and whose classes’ enrollment has also taken a serious dip, is facing none of these consequences.

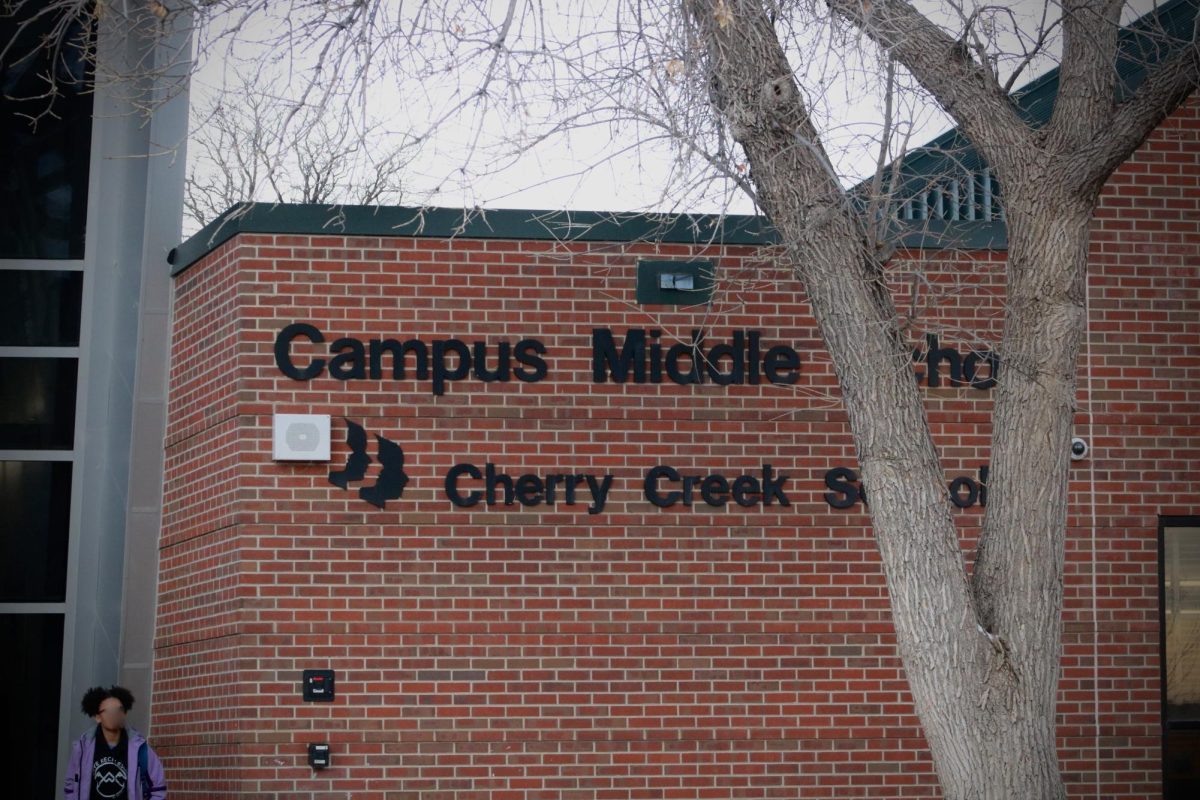

As a side note, in a seemingly unimportant scene, Rentz’s wife briefly mentions how she was once up for tenure — but didn’t quite get there because “someone had to make dinner” for their children. And she seems to think this is perfectly normal. This isn’t an uncommon issue, either. My mother’s history department at Metropolitan State University of Denver tenured its first female professor with children only six years ago — that makes my mom just the second tenured mom. This isn’t even the result of overt misogyny, by the way, just a reflection of the systemic obstacles in place for working mothers in academia – it’s harder for them to clear crucial professional hurdles such as finishing grad school, finding tenure-track jobs, and earning tenure.

Meanwhile, Ji-Yoon is facing single motherhood of an adopted daughter who is of a different race than her, and her main sources of childcare come in the form of her old-fashioned immigrant father and Bill Dobson. Her daughter, Juju (Everly Carganilla), gets suspended from school after repeatedly acting out, and Ji-Yoon finds herself divided from her elementary school daughter in a way that seems insurmountable.

Ji-Yoon is, as our hero, not perfect. She doesn’t always know the best thing to do. She is caught between her care for her colleague and friend, her realization that he’s done the wrong thing, her need to be there for her daughter, her sense of duty to her women and colleagues of color who Pembroke is failing to support. And, often, she doesn’t make the right decision. It’s what makes her character so easy to sympathize with.

Sandra Oh herself is the daughter of Korean immigrants to Canada. Before the show aired, she often spoke candidly about what that was like growing up. She’s also spoken about what it’s like to be a woman, a person of color, and a woman of color in Hollywood. Her character Cristina Yang made history in 2005 as one of the first Asian-American characters to appear in a lead role and not be heavily stereotyped. Cristina was unapologetic, and so is Oh. But Ji-Yoon is not. In fact, one of Ji-Yoon’s character flaws is the difficulty she faces in standing up for herself and for what’s arguably right — although this tendency also reveals the pressure she’s under as a female academic of color. And Oh plays the part so well – we never doubt her performance for a second.

The Chair is awkward. It’s crude. But not in a bad way. In a way that forces you to reevaluate cultural norms and issues we face every day. In a way that makes professors feel heard and makes students think about what’s actually going on behind the scenes.