How We Can Stop the Burn

South Metro Denver could be at risk of something similar to December’s disastrous Marshall Fire. Can we lower our fire risk?

An American flag stands on a burned property in Old Town Superior. The Old Town neighborhood was among a few burned entirely to the ground in Superior and Louisville, Colorado, in the Marshall Fire, which swept Boulder County Dec. 30.

March 2, 2022

When Boulder County went up in flames the day before New Year’s Eve, it caught the community by surprise in about a dozen different ways. It was months after fire season, and the homes burning were mostly suburban, or, as one resident put it to the Washington Post, “200 yards from a Costco.” It was unprecedented.

But the Marshall Fire, which destroyed 1,118 structures and killed at least two people on Dec. 30, may not have been as out-of-the-blue as it seemed. And it may not have been the last of its kind.

In the weeks following the fire, many have asked questions about how the tragedy could have been prevented, or why it happened, or if it had roots in climate change. Some of these questions can and will be answered. Others are more complicated. But what has become increasingly clear is that something like this happening again is not at all out of the question, and more than just Boulder County communities are in danger.

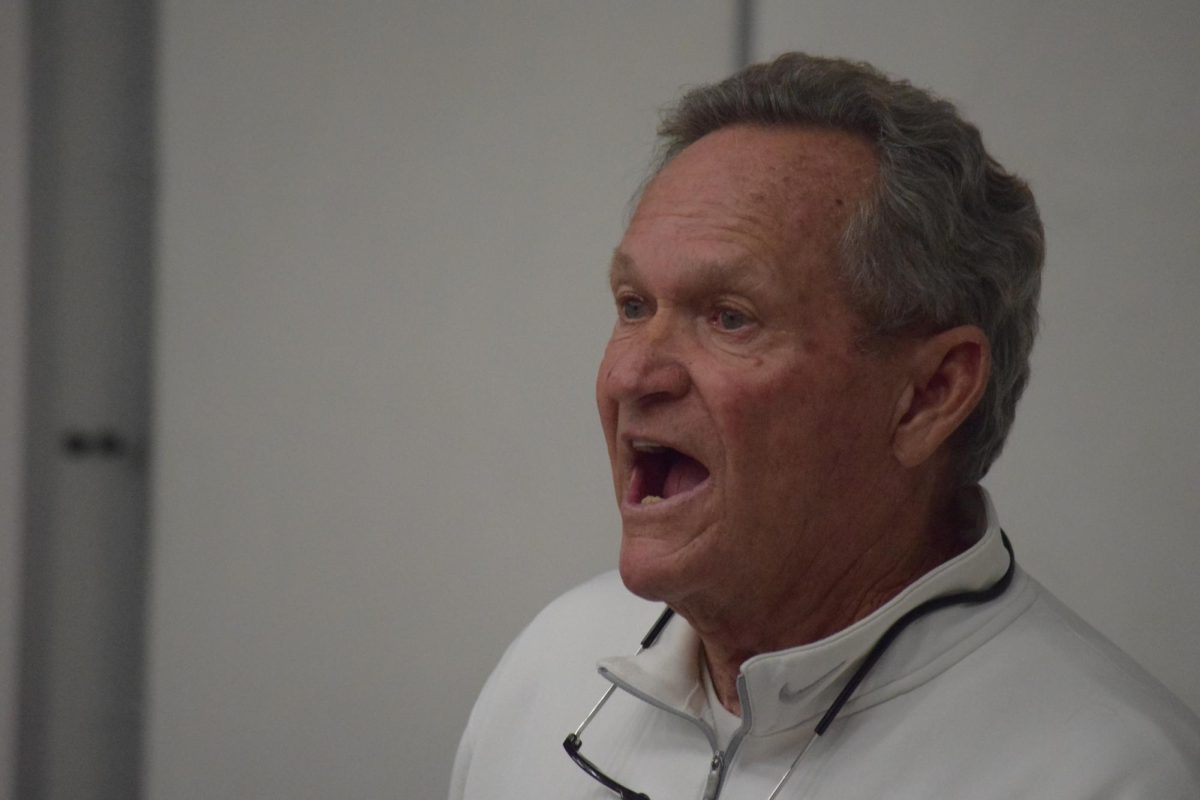

In the South Metro Fire District, which includes Creek and most of its students, wildfire is a very real risk, even if it might not burn hundreds of homes at a time. According to South Metro Fire Rescue (SMFR) Risk Reduction Specialist and former Clear Creek County firefighter Einar Jensen, a main concern for the SMFR are “low to moderate intensity fires.”

“Those are fires that are not powered by hurricane force winds,” Jensen said. “They certainly burn in our ecosystems, within our fire districts, and they burn fairly regularly. Last year, we had a little under 100 wildfires in our district. The year before that we had about 140 wildfires in our district.”

Jensen said that while these fires are usually under an acre in size and rarely harm people or property, they do have the potential to become more severe. And what’s more concerning to SMFR, and the reason that risk reduction specialists exist, is that nowhere is safe from wildfire within the district. Even fires burning miles away have the potential to harm neighborhoods.

“We could have a fire burning on the Hog Back, the west part of our district, or burning in the backcountry wilderness area or burning on the bluffs just south of Lone Tree, for example,” Jensen said. “Depending on the weather, depending on the amount of heat being released by the fire, those embers could fall anywhere in our fire district.”

In the Marshall Fire, hurricane-force winds – often above 100 miles per hour – blew embers and flames eastward at an aggressive pace, forcing the fire across open fields and into neighborhoods within minutes. One neighborhood – the now-flattened Sagamore development – burned in just minutes because of these winds.

“Without that wind blowing [the fire] through those neighborhoods, the fire would have been completely different and may not have burned any structures,” Jensen said. “It could have been stopped faster and safer.”

Jensen said that winds of those speeds are less common south of Denver and are unlikely to spur a fire of that size. What makes fire dangerous in this region is not so much weather, but lack of preparedness.

“Just because a person lives in a city or the suburbs does not make them safe from wildfire, because of the ember risk,” Jensen said. Later, he added, “The majority of homes across the nation ignite from embers that are cast downwind of a wildfire.”

Much of Jensen’s job is raising awareness about fire danger and prevention to make communities safer. And there’s a lot residents can do to make themselves safer.

Fires are fed by fuel. Both vegetation and structures can provide this fuel. When the fuel is packed close together horizontally, it’s easier for the fire’s heat to radiate from one thing to the next, spreading the flames at a much quicker rate. Incombustible materials like metal fences can conduct this heat, eventually burning whatever the material touches, but what’s most dangerous is when vegetation is planted too close to a structure or the structures are too close together.

One part of this is fairly easy to fix. Jensen said that vegetation, especially highly combustible plants such as junipers, should be planted at least 30 feet away from structures. Plants like this are a notorious fire risk. Jensen calls them “little green gas cans.”

“A juniper looks green, but…it’s full of resins that ignite quickly – extremely flammable,” Jensen said. “We call those ‘little green gas cans.’ If you have a juniper within 30 feet of your building, that is a ginormous risk to that building and to the occupants of that building. You take out the juniper, you reduce that ‘little green gas’ can outside of your building, now your building is far more resistant to wildfire.”

In Colorado, residents of “wildland-urban interfaces” are able to deduct what it costs to lower flammable vegetation risks around their property from their state income taxes.

There are other simple ways to reduce fire risk. “It’s pretty easy, in theory, depending on your fear of heights or ladders, to clean out the gutters surrounding your building,” Jensen said. “Clean out the dead needles and the dead leaves, and that reduces a trap for embers to fall and start a small fire right at the roofline.”

Homes can also be built with more fireproof materials, said University of Denver assistant professor Eric Holt, who specializes in construction management.

“Because of the fire, everybody’s now questioning the traditional building products,” Holt said, remarking that other areas like California have already been having these conversations for a while. He said some of it is about what we make walls out of. But even if homes are built with nonflammable exteriors, it’s not completely safe.

“If you got a broken window, or you got poor ventilation, or your roof vents or the dryer vent…anywhere that a spark can enter inside another system or a penetration within that wall, now you burn the inside of the house out,” Holt said.

Holt doesn’t believe that fireproof building techniques will really catch on unless fires like the Marshall Fire become more common. And even then, it’s nearly impossible to build something that can’t catch fire. “It’s a challenge to build completely 100 percent fireproof,” Holt said. “That’s a concrete bunker.”

And other pieces of the fire prevention puzzle are similarly complex. Much how closely packed vegetation can spur a fire, so can closely packed structures. In many areas in suburban Denver, developments from the last several decades have homes just a few yards apart. In Superior, where around 9 percent of housing stock burned down during the Marshall Fire, the Sagamore neighborhood’s homes were built closely together with large trees in between and small yards. This could have contributed to how fast it burned. Not a single home in the Sagamore neighborhood is still standing.

Some neighborhoods in at-risk areas such as Highlands Ranch and Aurora look similar, where closely packed houses often border large greenbelts or combustible grasslands.

But solving this problem is complicated, Jensen pointed out. Building homes farther apart can result in more intrusion on the open space that is necessary for healthy ecosystems. “The challenge is if we decide that homes must be further apart from each other,” he said, “that means that our built communities are going to grow bigger, right?”

Studies have shown that structures built within a quarter mile of open space are at much higher risk from fire. But Jensen said that logic is flawed, and the insinuated solution is flawed, too.

“So you take out that quarter mile of homes, you put open space in there, and now you have another quarter mile of homes that are exposed to that open space, right?” he said. “So unless we pave that quarter mile, we’re still gonna have the open space right next to homes…this is the reality of where we live. We don’t live in Disneyland. We live in vibrant, dynamic ecosystems where even though we built human structures, we still have to deal with our ecosystem. The wind doesn’t stop at the town limits.”

So residents’ best chance is in their ability to create more fire resistant communities using the kinds of resources and techniques that Jensen promotes. And the Marshall Fire is an all-too-telling tale of why it’s necessary.

Longmont Fire Department Engineer Billy Masterson fought the Marshall Fire while it was burning. A resident of Louisville, he described the harrowing experience of driving through his own community as it burned.

Masterson and his crew were assigned to a particular area, forcing them to pass other homes that they couldn’t save. “We were struggling to pass these places,” he said. “Just seeing everything that was potentially flammable – it looked like those things were all on fire. And each one of those was a massive event in its own right.”

The Marshall Fire was nearly unstoppable. Masterson described how he and his crew would drench homes in water before they could burn in order to save them. Some of those structures are still standing. Others aren’t.

“At one point I ended up in a neighborhood with some very close friends’ [homes] who were neighboring the houses that were on fire, and we spent a good portion of time flowing thousands, if not millions, of gallons of water into these fires, and it was to really no avail,” Masterson said. “It ended up burning right around what we were doing and just went into the places that we were trying to stop it from going into…it was all because of the wind.”

According to Masterson, fires are a well known risk in that region. “I think we’re aware,” he said of the risk of wildfire in Boulder County. “What we weren’t expecting is for [the fire] to extend into neighborhoods and cause this big a problem. [Grass fires], typically, you think you can stop them. But with the combination of how much heat was produced, because the wind was pushing the fires and involving so much grass so quickly, it created really big flame fronts, to the point where it could cross Highway 36 really easily and throw embers for hundreds of yards, if not miles.”

Masterson’s experiences and the thousands now rendered homeless due to the fire are proof of why it’s important to do our best to reduce fire risk.

SMFR, which is well aware of the risk of wildfire in the district, trains all of its firefighters in wildfire management. They have special protocols for “red-flag days,” when the weather is especially conducive to wildfires, and some stations are equipped with vehicles that are used to fight grass fires. They’re also active in reducing fire risk as a whole: the department has sunk countless dollars into fire prevention and education. One piece of this is risk reduction specialists like Jensen, who visit schools and other community areas to discuss fire risk and often act as press liaisons. There are five of these specialists in total: one for every battalion, essentially a region, of SMFR.

Jensen said one of their goals as a district is to become a fire adapted community. SMFR is one of hundreds of communities across the country working on becoming a fire adapted community, a term coined by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. According to fireadapted.org, “fire adapted communities are knowledgeable, engaged communities where actions of residents and agencies in relation to infrastructure, buildings, landscaping and the surrounding ecosystem lessen the need for extensive protection actions and enable the communities to safely accept fire as part of the surrounding landscape.”

Jensen said that something like this is important, because wildfires are not inherently bad – in fact, they’re necessary to keep most ecosystems healthy. But the extent of damage seen in fires like the Marshall Fire is something Jensen seeks to avoid.

“I don’t want to prevent wildfires in our fire district. I want wildfires to continue burning, but burning in such a way that they’re easily and safely herded or managed by firefighters,” he said. “So we get the ecological benefits without the structural damage, the infrastructure damage, or the injuries and deaths.”

It’s also valuable to understand the roots of wildfires. Studies have shown that upwards of 90 percent of wildfires are human-caused nationwide. In Colorado, this number is 97 percent. Many of Colorado’s most disastrous wildfires in its history have human causes. The Hayman Fire, a 2002 blaze that was Colorado’s worst for 18 years and killed six people, was caused by arson. The Cameron Peak and East Troublesome Fires, which burned for multiple months in 2020 and claimed the first and second place spots, respectively, for worst Colorado wildfires, are both believed to have been caused by people, though they’re both still under investigation. And the Marshall Fire, which will likely be under investigation for a while, almost certainly had human causes, early reports show.

In South Metro, nearly all wildfires have some human cause behind them. Jensen said that a lot of this is kids intentionally or unintentionally setting fires, highlighting the importance of fire education for young children. Fireworks are also a big factor, though they’re not supposed to be. “In Colorado, any firework that leaves the ground is illegal every day of the year including the Fourth of July,” Jensen said. “So stop using illegal fireworks. That would make a huge difference.”

But equally as important as reducing your fire risk, Jensen said, is being prepared. Because if a wildfire is threatening your home, you don’t want to be caught by surprise.

“I talked to my daughters, who are 13, about evacuation and what that would look like, and they asked me, ‘What about our pets?’ So we had frank conversations about which pets can go and which pets should stay,” Jensen said. Jensen’s daughters have many animals, including dogs, cats, lizards, birds, fish, a chicken, and rabbits. In case of an emergency where their home is imminently threatened and they only have minutes to get out, Jensen said grabbing many of their animals would be impractical and dangerous. So their plan is that if they need to leave in a hurry, they’ll grab the dogs, cats, and rabbits. It’s heartbreaking, but it would be worse if they didn’t have a plan.

Jensen added that in the case of a fast-moving fire, it’s good to have in mind what necessary items you’ll take with you. “When you’re thinking about your evacuation, you want to grab the dirty clothes hamper because all those clothes fit, and if you just reached to the closet, you might grab stuff that doesn’t fit,” he said. “So you grab the clothes in the hamper. You got to grab your medicines, you gotta grab your reading glasses, you got to get your hard drives.”

Thinking about what you’d have to leave behind in case of fire is emotionally draining, but it would be worse if you were caught off guard.

“It’s hard. And it’s the pits,” Jensen said. “ You only think about it because that helps you go through the muscle memory of trying to figure out what you’re going to do. So if you ever have to do it, you’ve got a leg up.”

But Jensen hopes that the knowledge he spreads through community programs about potential risk and how to lessen the danger of fires to your home will help more and more people avoid the unthinkable. Because despite how scary fires are, we have tools to make it not as scary. And we have a responsibility to use those tools, both for ourselves and our communities and ecosystems.

“I mean, we’re here. I love being here. I’m a native Coloradan,” Jensen said. “I don’t want to leave just because of wildfire potential. But I think that we can do better.”

This article won Honorable Mention In-Depth News Coverage from CSMA. The photo “All That’s Left” won First Place Print News Single Spot News Photograph from CSPA and Second Place News Feature Photo/Caption from CSMA.