The untold story of the Columbine shooting

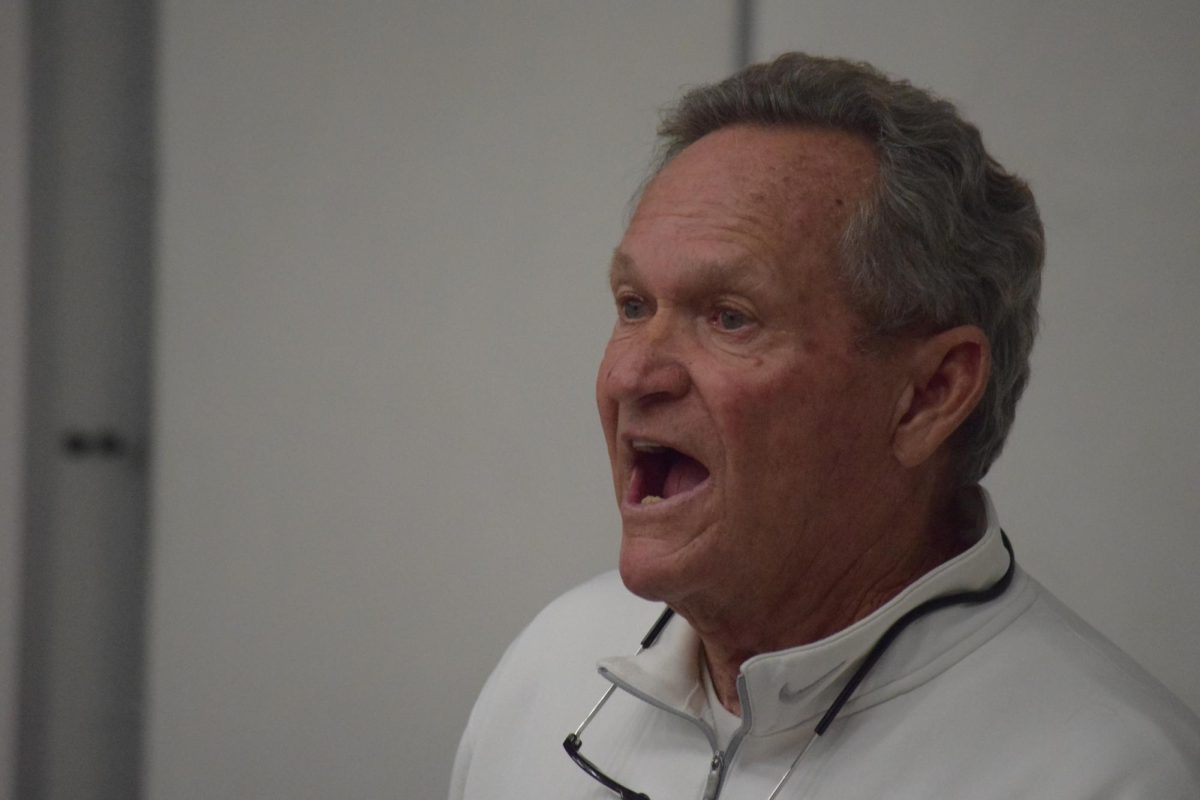

Woolsey reflects on his freshman year at Columbine

Photo courtesy of Fletcher Woolsey

Photo courtesy of Fletcher Woolsey

November 16, 2016

On April 20, 1999, Columbine high school was terrorized by two teens, who shot 33 people, resulting in 13 deaths. The traumatic event led to a national awareness of teen depression and gun violence in schools, but more importantly it introduced a stronger relationship and better communication between the student body and the staff for schools in the US.

Today at Cherry Creek high school we have very good teacher-student relationships and many resources for the student body to find help if needed, but it wasn’t always like this. In 1998 through 1999 “teachers didn’t go as far out of there way to worry about [students] personal problems” says Fletcher Woolsey, U.S history teacher at Creek, on his freshman year in high school at Columbine. “Whereas now I think about being a teacher, and I look at it and say I would really investigate that more, especially if it were a good student who just stopped turning in homework. I would be calling counselors, I would be calling home and that really didn’t happen.” Teachers in 1998 and 1999 would ask good students, such as Woolsey a simple question, “are you okay” if any unusual behavior in classes would occur, but when the students would say, “I am okay” teachers would leave it at that.

Woolsey says his first year at Columbine was just like any other freshman’s year. He went about school life as “the low man on the totem pole like freshman always are” and heard the occasional rumor about upperclassmen hazing freshmen. Most freshmen were scared of the upperclassmen because of the vicious rumors that spread throughout the school that threatened lowerclassmen with being taped to a chair, or taped to the flagpole. Most of these problems went unnoticed by the staff and teachers because of the lack of proper communication between the teachers and students. “I have a pretty strong feeling if I would’ve said something to my teachers most of them probably would’ve been like, “oh yeah! Well, upperclassmen can be jerks,” basically just [saying]“suck it up kid,” Woolsey said.

After the shooting there was definitely more of a caring atmosphere and an understanding because of the traumatic events that occurred. “Especially in the year immediately following the shooting, I think that there was a little bit more empathy among the students,” Woolsey said. “When you saw the young sophomore girl in tears in the hallway, you would stop and ask her if she was okay, or you would take her to the counseling office. Whereas before [the shooting] you would say oh, she is being dramatic, she is being a typical tenth grader, whatever her boyfriend must have dumped her, I have better things to worry about.”

Woolsey completed his high school career at Columbine high school just like any other student. “For each of the remaining three years, I had at least one classmate that either died or took their own life [which became a] very sick annual tradition,” Woolsey said.

“Every threat or joke needs to be taken seriously…and that can seem borderline oppressive at times, but it’s always the one that you don’t take seriously that comes back to bite you,” Woolsey said. It’s important to know that “a lot of times in the teenage brain its really easy to feel like the world is against you, and if you are a teacher or administrator you may think that you are always sunshiny and optimistic, but you have to remember that some people in high school could feel like everything is against them. “Its going to take more work than just a friendly, are you okay?” Woolsey said. We can accomplish anything if we apply ourselves to this issue and really reach out to people in that state of mind.