Every cheesy high school movie starts the same. An overwhelmed shy girl is shown the school cafeteria via a map handed down by newfound friends. Jocks in one corner, nerds in another, and the popular cheerleaders all on their own. Although humorous and oddly dystopian, this perspective has a real life basis.

Students at Creek can be seen grouped up everywhere, but instead of the stereotypical football fanatics, it’s by race. Teenagers can be seen gathered around and making friends with people that they physically relate to, in and out of school. It’s a subconscious decision we make because we’re psychologically drawn to people that are similar to us.

“Me and my friends have a lot of shared experience, from our culture, to home lives, to experiences in general,” junior Angie Wang said. “We get along well because of it, and we have a lot to talk about with each other.”

This concept, people being drawn to others who are similar to themselves, is called homophily. It played a big role in early history when people were focused on increasing the chances of surviving. By forming communities, people could eliminate any chance of outsiders infiltrating their home. This type of behavior remains within ourselves and has continued in our society.

“Probably a good 70% of my friends share my race,” junior Elliot McGrath-Imbert said. “Out of my closest friends, I would still say most of them are my own race.”

According to a survey done by the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health focusing on middle and high schools, the average odds of teens listing friends of the same race is two times more likely than the odds of them listing friends of a different race.

“I accept that being a non-white person in America will mean being surrounded by white people that I’ll struggle to identify with,” Wang said. “I’m thankful that Creek is more diverse compared to other schools I’ve been in.”

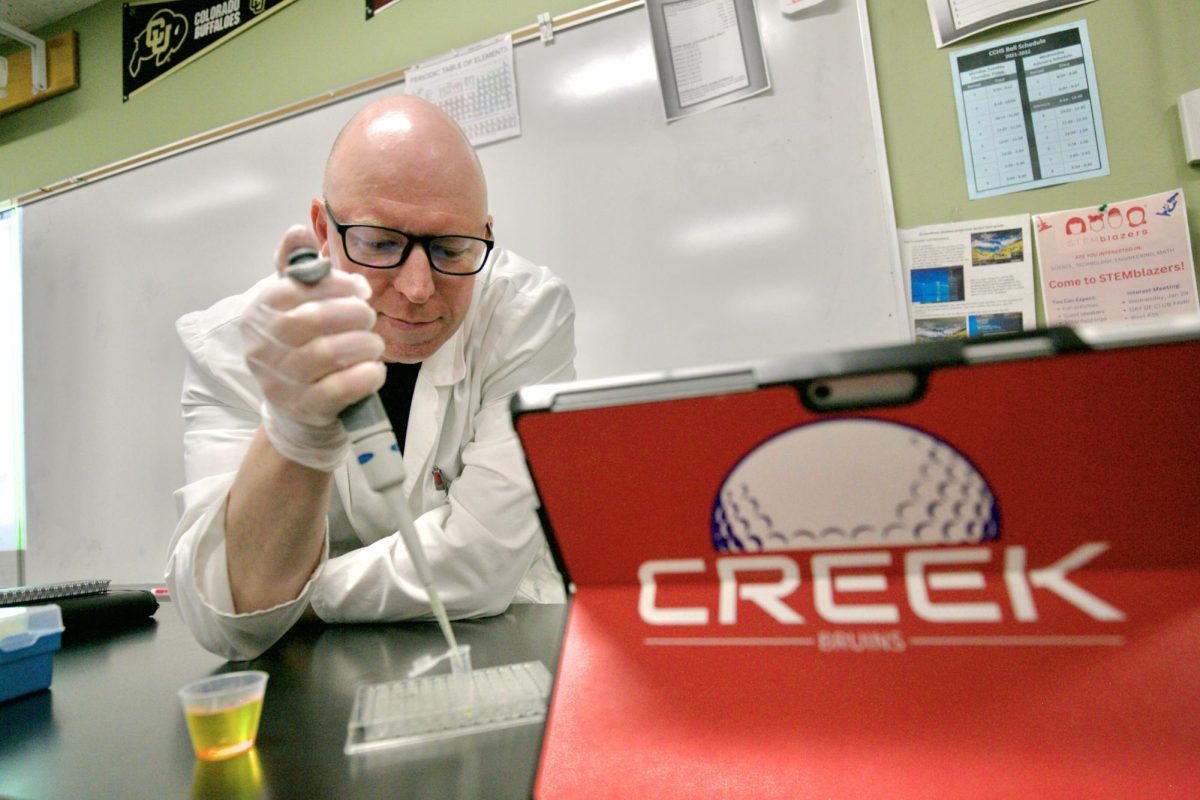

With Creek’s student population of about 4,000 kids, students tend to group up together according to their physical appearance, resulting in voluntary social segregation around school. That doesn’t mean diversity doesn’t exist within social clusters, but there is an apparent pattern.

“I became friends with most of that third [of Hispanic friends] while I was living in Miami because of the demographic,” junior Valentina Lazardo-Bracho said. “With the few Hispanic people I’ve become friends with here, it’s been mostly due to similar culture.”

Since survival isn’t as difficult as it used to be, people tend to group up more out of a sense of security and familiarity than anything else. With Creek being a predominantly white school, with 64% of students being white, students of color instinctively reach out and connect with people most similar to them.

“If I had to describe [my Creek experience] in one word, it would be lonely,” Lazardo-Bracho said. “I feel that our cultures differ a lot in how open we are with each other, which is why when I first moved here, I had a hard time making friends.”

In the beginning, most minority students felt left out or alienated from the rest of the student body. The majority wasn’t where they fit in, so they form their own little groups and find familiarity and comfort with each other so that the feeling of loneliness becomes one of indifference.

As people continue to seek out those most similar to them, societal segregation can remain. For some students, grouping with others of their same race is a way to find community and people to connect with.

“Finding those who share experience with you gives a sense of closeness and comfort and brings people together,” Wang said.