To senior Carissa Pomeroy, sex education (sex-ed) means more than awkward conversations about condoms. For her, it’s a way to learn about the government and, more importantly, prevent sexual assault.

“I feel like so much of sexual assault can be prevented with proper education and breaking down conservative views of sex,” Pomeroy said.

Pomeroy joined Colorado Youth Congress (CYC), an organization run by high school students, right before her junior year, hoping to pad her college resume and bring awareness to issues she’s passionate about.

“We have a lot of good initiatives that we are focusing on like immigration policy and ways to implement environmentally friendly programs in schools.” Pomeroy said. “I’m specifically a leader for sex-ed, because it’s the one thing in the whole organization that I care about.”

Pomeroy wanted to use her spot in the CYC to spread awareness about sex-ed in schools.

Now, her work is centered around finding a way for sex-ed to be basic information for high schools to teach to students.

“[The] idea was to have a better sexual education,” Pomeroy said. “We started last year and now we’re working on pushing that to be something.”

And for Pomeroy, that “something” has been neglected for a long time.

“I know so many girls throughout my life that don’t even know that there are two holes in a vagina and people are too scared to say it,” Pomeroy said.

The process of getting sex-ed to be talked about more has been difficult. Pomeroy has to navigate conflicting opinions from school communities, made up mostly by parents, to fight controversy around the topic.

“A lot of the people who have that view are religious and there’s a lot of immigrant parents who don’t have that liberal view. It’s not a normal thing in their lives,” Pomeroy said. “But it pisses me off. Because how else would you learn about it [without] experience?”

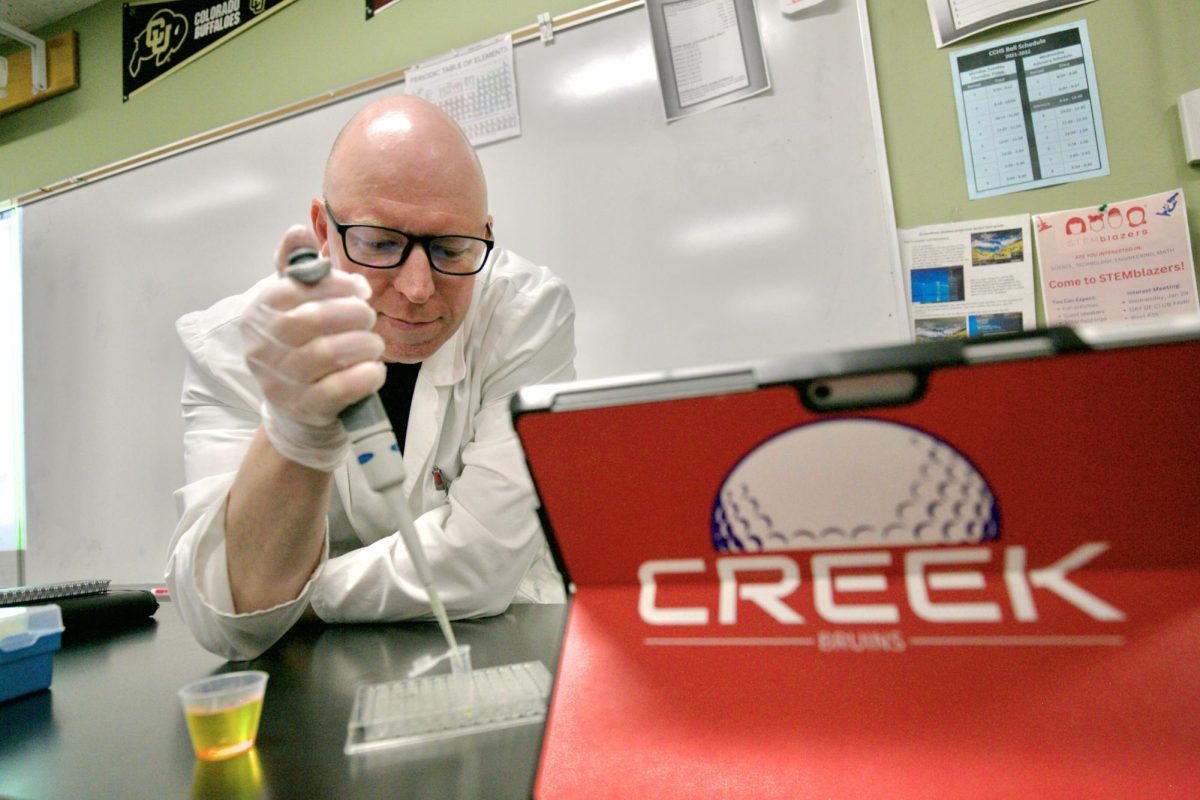

Controversial opinions from parents also exist at Creek.

“I don’t think I would bring it to Creek right now, just because the type of parents that are here are way more involved than DSST (Denver Schools of Science and Technology) city schools,” Pomeroy said.

Pomeroy and her team are currently in the research process and are working towards getting government officials involved.

“Our angle last year was to get legislation passed that required a comprehensive and inclusive sex-ed program in every Colorado school,” Pomeroy said. “We spent the bulk of our initiative time just researching and gaining connections.”

Pomeroy’s team works with an organization called Trailhead Institute, an organization that implements pilot programs into schools that may not have sex-ed to test it out.

“School curriculum and community also makes a difference on where this course could be offered,” Pomeroy said. “Schools that don’t have [an existing sex-ed class] are more willing to try it than schools that already have a program in place.”

Pomeroy also wants to bring diversity to the curriculum.

“The biggest thing we also wanted to focus on was to incorporate LGBTQ+ representation,” Pomeroy said. “[We want to] navigate [what] that kind of world is like for someone who could be trans, [and] could be doing sexual activities.”

Instead of making a separate sex-ed class, Pomeroy would rather incorporate it into a pre-existing health curriculum, altering it to be more comprehensive.

“[Students] should have the choice to take it anytime they want,” Pomeroy said. “I feel like more people would be willing to take a class like that if they had that voluntary choice.”

Pomeroy strongly believes that sex-ed is crucial for people to learn because it can introduce them to key things about themselves, not just sex.

“Sexual education is not just sex and biology, it’s also about your own identity,” Pomeroy said.