Rethinking the Grade: Teachers Push For More Equity

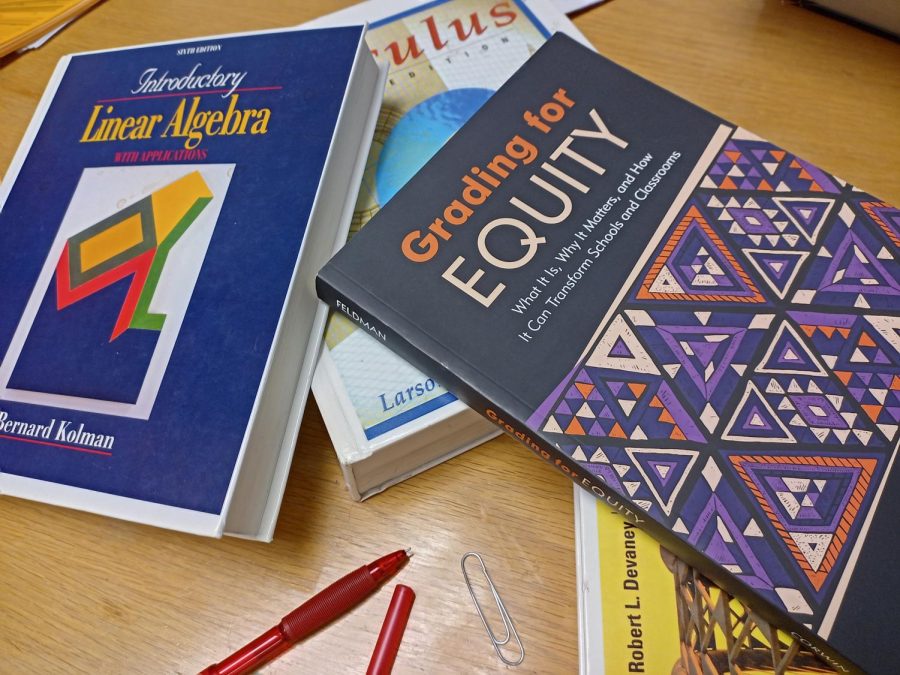

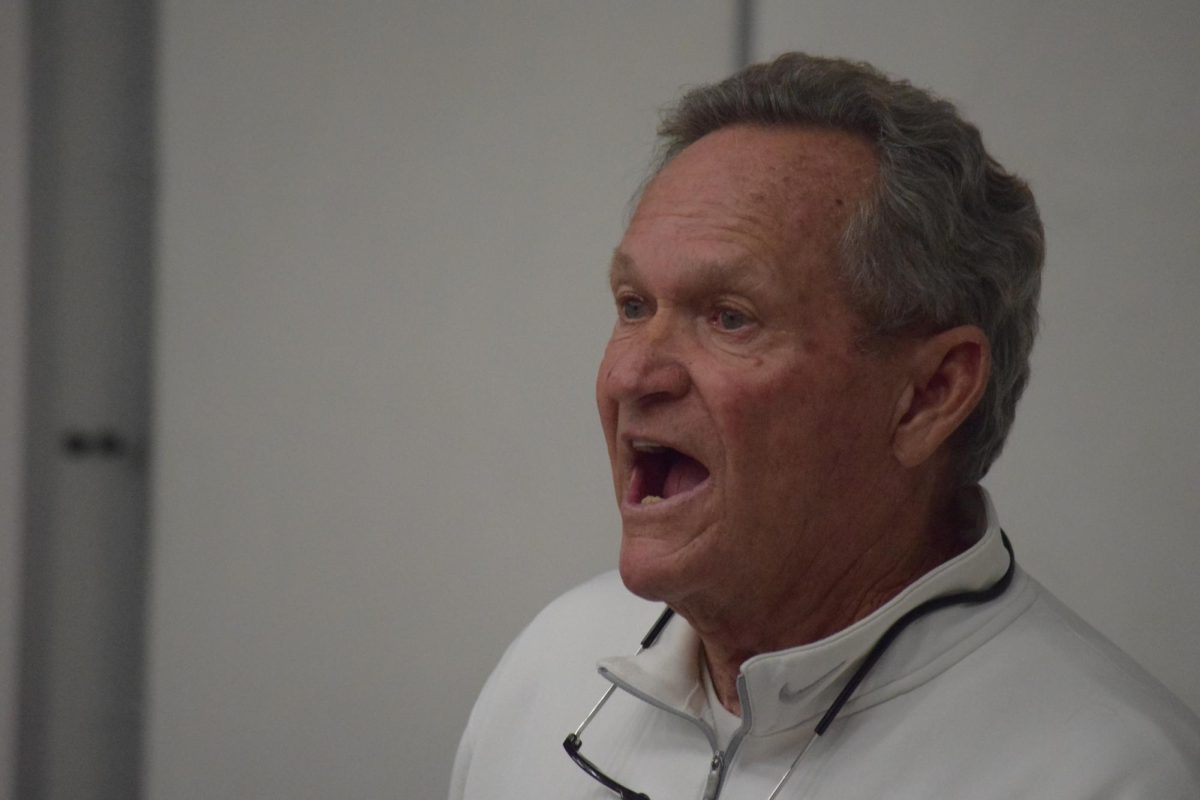

Math teacher Robert Matuscheck teaches Calculus 3 Honors, Differential Equations Honors, and Linear Algebra Honors while also being a facilitator for the Evidence Based Grading (EBG) Group at Creek. He, like all members of the EBG Group, works towards implementing equitable grading practices in his classes.

March 15, 2023

With late assignments piling up in your PowerSchool, you dread the day the “missings” will turn into “zeroes,” plummeting your grade to an abysmal level. Then you remember one critical detail: your teacher always accepts late work for credit.

A lenient late work policy is one of many Evidence Based Grading (EBG) strategies. Teachers who employ EBG in their classrooms, including Creek’s EBG Group members, intend for student’s grades to directly reflect their knowledge of the curriculum – not any other outside influences which might, for instance, cause a student to turn in an assignment a month late.

The EBG Group, created in 2020, is composed of teachers who meet to discuss what EBG strategies and other classroom practices could be used to allow every student an equal opportunity to get a good grade regardless of any advantages or disadvantages they may face.

English teacher Emily Cave is one of the teachers who first piloted the group in 2020.

“It was just a bunch of teachers who were realizing that we needed to do something different because kids had skills that weren’t reflected in grades,” Cave said.

A survey conducted by the EBG Group revealed that African American/Black and Hispanic students were overrepresented within the group of students who received a D or F during the Fall Semester of the 2022-2023 school year.

According to Rob Matuschek, math teacher and one of the EBG Group’s Facilitators, moving away from traditional grading and adopting more equitable grading techniques is a step toward closing the achievement gap at Creek.

Cave believes that EBG accounts for the different levels of access to material and support students have outside of the classroom.

“Students come in with different support systems from home,” Cave said. “So there’s no penalty for students who don’t know anything coming in versus the kids who had a tutor over the summer.”

Another member of the group, science teacher Kenadi Dixon, implements EBG in her CP Biology class, where she gives students a 50% as opposed to a 0% for work they don’t hand in, and allows them multiple attempts on quizzes in order for their educational growth to reflect in their grade. One of Dixon’s current CP Biology students, sophomore Jazz English, feels the benefits of these policies.

“It’s really helpful for me … I learn better from my mistakes,” English said. “It’s really based off of what you learn rather than what you can just put on a piece of paper.”

What helps one student in one class, however, may not be as effective in another. For that reason, the EBG Group doesn’t specifically require teachers to implement anything in their classroom a certain way. It’s the same reason EBG isn’t a school-wide policy.

“A grade book then is an extension of the teaching that you do,” Assistant Principal Marcus McDavid said. “And therefore, Mr. Silva has said ‘I want to still embrace that philosophy of being able to let the experts—the teachers—design the instruction in a way that fits them.’”

Regardless of whether or not they are in the EBG group, teachers are encouraged to be conscious of how their grading practices may influence their students. For instance, on Feb. 21, in the last hour of Professional Development Day, teachers talked about the purpose of grades, both through the lens of EBG and as more of a general conversation about eliminating disparity in achievement.

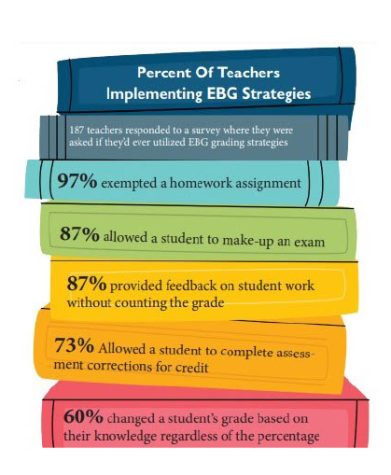

“Everybody’s doing it,” Matuschek said, citing another one of the EBG Group’s survey results which revealed that every teacher surveyed had implemented one or more EBG strategies. “Most teachers in the building engage in [EBG] in one form or another – the team is taking all these things and doing it formally.”

What makes the EBG Group unique is that it provides members with support and access to shared knowledge learned over collective years of being educators.

“I’m grateful to be a part of that team and to work with just amazing educators from all backgrounds with various years of teaching experience,” Dixon said. “I think we each bring something unique to the table, and because of that I think we’re better for our students and better for Creek.”