On 9/11, Life At Creek Screeched To A Halt. 20 Years Later, These Teachers Still Remember It All.

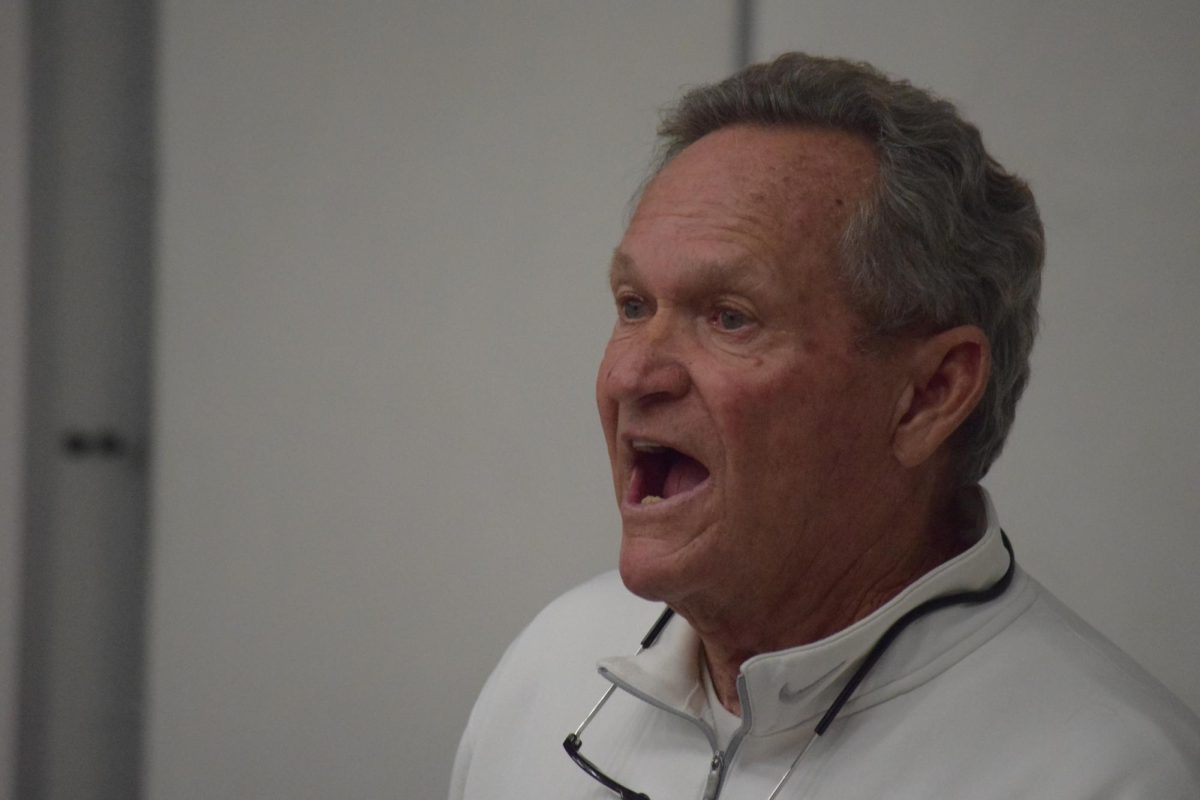

Messages to those affected by the 9/11 attacks featured on the bottom of the front page of The Union St. Journal’s Sep. 20, 2001 issue. Due to the long turnaround time of a high school newspaper, students were unable to feature more stories on 9/11 in the September issue, but filled the front page of the Oct, 18, 2001 issue (below) with 9/11-related articles. For teachers, supporting students – and figuring out how to manage their own emotions – was difficult. “We were instructed that counselors would be available should anyone need to talk. It felt like a surreal kind of dream,” math teacher Jim Padavic said. “Once they [the Twin Towers] fell, there was a helplessness and sadness and disbelief that this could happen in America. The visuals of firemen and policemen volunteering to enter the towers to help followed by the collapse of the towers was gut-wrenching.”

September 11, 2021

It’s hard to think back 20 years.

Twenty years ago, not a single current Creek student was born. Many current Creek teachers were in college or grad school, scattered across the country. Only a handful were at Creek.

Twenty years ago, 2,977 victims were killed in a terrorist attack on the United States that would forever change the course of human history.

For those who lived through it, though, the memory of 9/11 is crystal clear. And if you ask any of the 35 current faculty who were here at Creek in 2001, they’ll tell you exactly what it was like to be at school that day.

Ask any of them, and they’ll tell you how the whole atmosphere at Creek shifted on Sept. 11, 2001.

“It was a Tuesday,” math department coordinator Cayel Dwyer said. “And Monday night [Sept. 10] was the start of the football season. The Broncos were pretty good back then, and so people were pretty excited. So it was like this big switch from one night into the next night. It was like a numb feeling.”

The morning of Sept. 11, 2001, everyone was talking about the Broncos’ victory over the New York Giants the night before. Principal Ryan Silva noted that the Broncos will be playing the Giants around the same time again this year – Sept. 12.

“The Broncos play the New York Giants this Sunday,” Silva said. “And the night before 9/11, the Broncos played the Giants. When I saw that on the schedule, I told my son about it. He’s 12, so no connection at all, right? He said, ‘Hey, this game is kind of symbolic.’”

Silva was a Spanish teacher in 2001. It was his second year teaching at Creek. Just like Dwyer, he spoke of the numb silence that fell over the whole campus.

“People were kind of dazed, in a fog,” Silva said. “Talking to each other in the halls about, ‘Can you believe what this is?’ And then sharing the information that they had heard, whether it was accurate or not.”

Some teachers equate the days after 9/11 to the days after the Columbine High School shooting in 1999, which had an immediate effect on Creek.

“All I remember was getting home that night [April 20, 1999], and just being utterly shocked by everything that was going on at Columbine, and it was the same thing with 9/11,” Dwyer said. “It was just numb. And all you could do was just go home and just try to filter what was going on.”

In 2001, as it was happening, 9/11 felt detached for many at Creek and across the West, so far away from home that it was almost surreal.

“Since it was so far away – I wouldn’t say we ignored it – but it almost felt like maybe it was being ignored a little bit, almost on purpose,” Dwyer said. “Because I don’t know that we were equipped to deal with emotions of what was really happening.”

Being so far away, especially without much of the technology we have today, it was difficult to know exactly what was going on.

“The information on TV was hit or miss for the first several hours, so no one really was sure what exactly had happened,” math teacher Jim Padavic said. “Cell phones were starting to become more mainstream and there were lots of messages going back and forth between victims and loved ones before the towers fell.”

Dwyer described how emotions developed as it became more clear what was happening – and more real.

“You know, [we saw] pictures of 9/11 and all the people covered in soot and smoke and the papers that were just flying everywhere,” he said. “And then President Bush goes to Ground Zero and [tries] to keep the spirits of the country up. It became a much different type of feel over those days. It took a little while for it to transition from shock, to grief, to action – ‘we got to do something about what happened.’”

Just like most American adults, Creek’s teachers can tell you precisely where they were when they found out. But the first plane hit the towers while the school day was already underway, so many teachers found out from their students, as the news spread that something terrible had happened. Many switched on the TVs that were mounted in every room at the time.

“My second period kids, some of them came running in the room,” social studies Kerry Moyer said. “My name was Miss Johnson then, and they were yelling ‘Miss Johnson, Miss Johnson, turn on the TV.’ And so I turned the TV on, and it was showing the replay of the second plane which had just hit the World Trade Center. I didn’t even know about the first one.”

Activities director Dr. Krista Keogh was a science teacher at the time. She too described how her classes crowded around the TVs.

“We all kind of just watched in awe,” Keogh said. “We didn’t know what we were watching and if World War III had just started on U.S. soil. We didn’t do much that day.”

Soon after, then-principal Dr. Kathleen Smith would come over the P.A. and tell all teachers to turn off their TVs. She wanted to make sure that students with parents or other family in New York, D.C., travelling, or in the airline business wouldn’t find out from a TV at school that their loved one was possibly dead.

Millions of people were in New York City and Washington, D.C. at the time of the attacks. And so many Americans, including Creek students and faculty, were immediately concerned for the welfare of their parents, siblings, friends, and spouses. Some teachers recall their students frantically trying to contact family and friends they knew were in New York.

“I remember one girl in particular,” Dwyer said. “She was like, ‘My dad works in New York a lot. He’s on a trip.’ And so I took her to a counselor, and allowed her to try to make contact with her dad. And she didn’t make contact with him immediately. But eventually, she was able to make contact with him. And he was okay.”

Nowadays, not a single Creek student has memory of 9/11 – not one of us was even born. We discussed it in middle school every year on the anniversary. Most of us know their parents’ stories – where they were when they found out, how it felt, the shock and palpable fear. But none of us can really know what it was like to live through 9/11. And for the teachers, it’s a strange feeling to have students who didn’t experience 9/11 at all.

“It’s probably comparable to how I was growing up with the Vietnam War,” Silva said. “I was born when it ended, more or less. And so it was something that I had always heard about, something that I remember adults having a really strong emotional attachment to, but I didn’t, because I just had seen it in pictures or in books and TV.”

Moyer brought up another major historical event that many teachers’ parents and grandparents – but few, if any, teachers themselves – lived through.

“It’s kind of like me trying to understand Pearl Harbor,” Moyer said. “It’s super interesting to me, but what made it more interesting to me was to hear from people who were alive when it happened, and to talk about what that was like when they found out that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. It’s really interesting, but it doesn’t seem to resonate with you as much as if you’d lived through it.”

As a social studies teacher, Moyer has since faced the unique challenge of trying to teach about an event that is so real in her own mind, but so abstract in her students’. This is difficult enough in a classroom, but becomes much more poignant when she tries to relate it to her daughters, the oldest of whom is only a sophomore in high school, born over five years after 9/11.

“I try to talk to my kids, and I think they think it’s a big deal, but they can’t relate to it in the same way that somebody who remembers it can,” she said. “I think a lot of times, for kids today, it’s history and it seems like a long time ago, but for those of us that were old enough to remember it, it doesn’t feel like it’s that long ago.”

Dr. Keogh finds that part of the surreality of having post-9/11 students is their lack of an understanding of the shifts that happened since 9/11 – because the students exist after it all.

“I forget sometimes that students don’t have a pre-9/11 frame of reference,” she said. “Although I truly don’t think most of our students for the past decade really remember what it was like ‘before’ 9/11. Things that seem different to me – like technology, travel, high levels of security – are just your normal. You guys don’t know any different.”

It’s undeniable that America has changed since 9/11. Directly after the attacks, the U.S. united around a common need for support. Everyone was grieving, and because of that, there was a deep sense of understanding, a kind of American nationalism that spoke of unity. But since then, many of those sentiments have soured. For adults who lived through 9/11, it’s all too easy to pinpoint how.

“Politically, things have become much more polarizing. And it’s not because of 9/11, that those things have happened,” Dwyer said. “But it did become a rallying cry, and as with all things, time tends to dampen some of those spirits. And so unfortunately, the nationalism that we felt, and the support of our nation, is a different type of nationalism now.”

Moyer spoke of the immediate effect the attacks had on some of her students after Islamophobic sentiments arose when it was revealed the terrorists responsible for the attack were Muslim.

“The Islamophobia really, really shocked me,” Moyer said. “I was so bothered by it and I had several Muslim and Middle Eastern students that you could just tell were hurting, and were uncomfortable being at school. It was just a weird situation.”

Moyer went on to talk about how scary the instances of Islamophobia got.

“We had a family at Creek, early in my career, that owns the Jerusalem restaurant, which is down right near DU [University of Denver],” she said. “It’s been around since 1978, and they had a giant rock thrown through their picture window at the restaurant after 9/11.”

Still, there were some students unifying around those who were being unfairly targeted.

“I co-sponsored a club called the diversity task force then,” Moyer said. “And so the kids were really involved in that club and I remember us having several meetings and things about Islamophobia after 9/11. Because, I mean, it’s still an issue, but it was really serious after 9/11. Those communities were really suffering.”

Since 9/11, there have been few situations where teachers have been put into a position where they’ve had to discuss such traumatic current events with their students. However, earlier this year, as the U.S. Capitol was attacked Jan. 6, many teachers struggled to figure out how to broach such a sensitive topic.

“I think it must have been the next day [Jan. 7], and I was talking to my students about it, and I was trying to be really careful with the way that I talked about it because it’s so politicized,” Moyer said. “It felt, as a social studies teacher, that it was critical that we do talk about it. It was interesting because it was online so that changed the dynamic a little bit. But the kids were really, really receptive and wanting to talk about it, and mostly it was them talking.”

It’s hard for high school and college students now to envision what living through 9/11 was like. But for those who did live through it, the memories are clear, and the effects will stay with them for life.

“I saw something the other day on the news, and it was a psychologist talking about how anniversaries of things like 9/11 create anxiety for people who lived during that time. I never really thought about that, but this whole last week I felt a little on edge and stressed out,” Moyer said. “I was thinking back on it – at the time, you’re just thinking ‘okay, this is huge, this is big, and it’s hard to process,’ but then you just keep going about life and you don’t really stop to think about how it affects you. But just being alive at that time and watching those images of what happened could create a little bit of post-traumatic stress or anxiety for people.”

![Messages to those affected by the 9/11 attacks featured on the bottom of the front page of The Union St. Journal's Sep. 20, 2001 issue. Due to the long turnaround time of a high school newspaper, students were unable to feature more stories on 9/11 in the September issue, but filled the front page of the Oct, 18, 2001 issue (below) with 9/11-related articles. For teachers, supporting students – and figuring out how to manage their own emotions – was difficult. "We were instructed that counselors would be available should anyone need to talk. It felt like a surreal kind of dream," math teacher Jim Padavic said. "Once they [the Twin Towers] fell, there was a helplessness and sadness and disbelief that this could happen in America. The visuals of firemen and policemen volunteering to enter the towers to help followed by the collapse of the towers was gut-wrenching."](https://unionstreetjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/IMG_2701-900x411.jpg)