#suicide

How social media impacts the way we think about suicide

November 16, 2017

On Tuesday, August 29, two Denver-area students died by suicide.

On Wednesday, August 30, another Denver-area student died by suicide.

On Thursday, August 31, another Denver-area student died by suicide.

Four suicides in one week, all within the first month of school, all within 28 square miles.

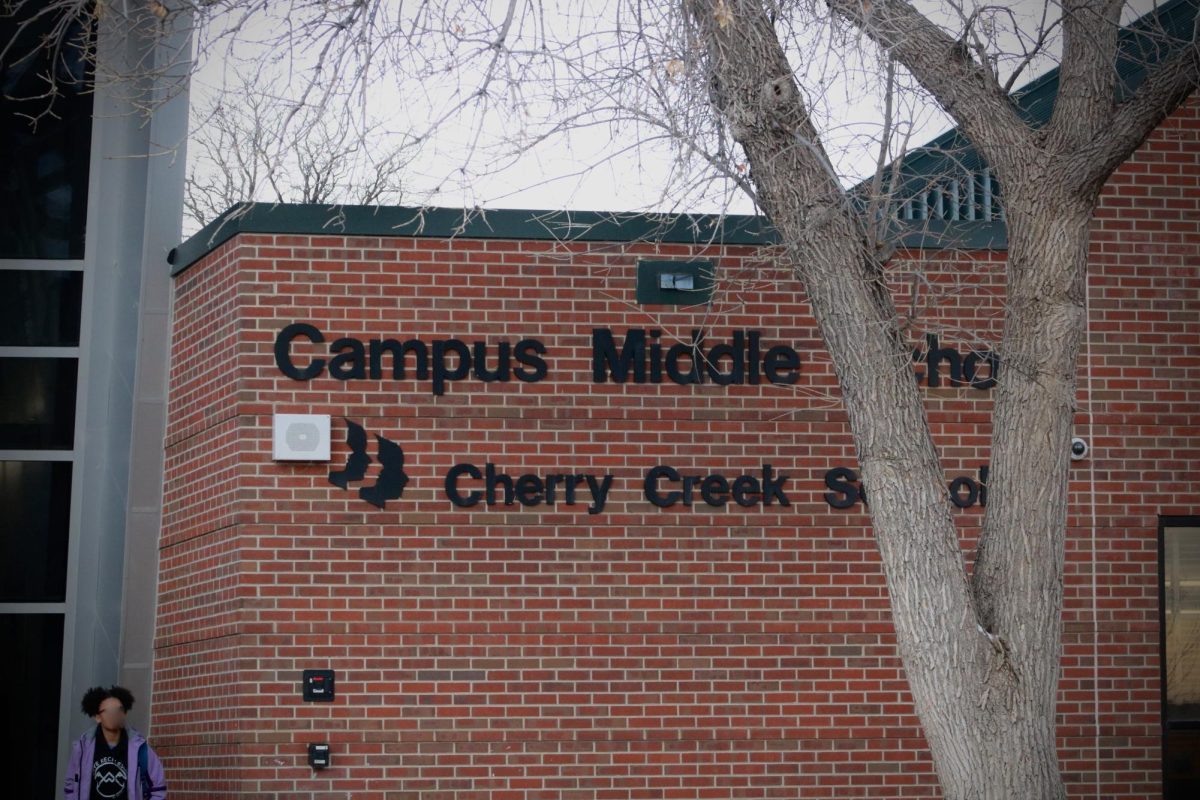

In the Cherry Creek School District, there hasn’t been the uptick in student suicides seen in neighboring school districts, but awareness has spiked through the use of social media.

“There may have been an uptick in reporting, not in actuality,” school psychologist Lisa Geissler said.

This may be due, in part, to social media and pop culture, and its ability to inform and raise awareness within the student body.

“[Social media] adds another level of stress, and it adds another level of disconnectedness,” Geissler said. “And yet it adds connectedness, in an ironic way.”

Beyond the potential impact of social media on depression and suicidal thoughts in adolescents, social media may be changing the way we view suicide as bystanders.

School psychologist Russell calls this the “contagion effect” and believes it may be altering how we consume or interpret the content we see on social media relating to someone who committed suicide.

There’s a virtual connection that did not exist prior to social media, where students relate to people they have never met.

“Now there’s a sense of, ‘I’m two friends away from that person, I’m practically friends with them,’” Russell said.

Sophomore Isabella Haddon said she feels impacted by hearing of suicides but not because of social media.

“It doesn’t make it feel closer,” she said. “If anyone commits suicide it doesn’t matter who the person is or if I know the person – it’s still suicide. It’s still connected to me no matter what.”

Still, mental health professionals worry social media is causing students to detach from their community.

“Something is happening where people are feeling disconnected, not just from family and guardians and people from school, but even isolated from friends and siblings,” Russell said.

Social Studies teacher Virginia Decesare has a very close relationship with her sophomore daughter but understands how a disconnect between student and parent could happen.

“I can see how you can get busy in your life and, especially if your kid seems to be getting good grades, seems to be doing okay,” she said. “You don’t see anything major or that they can get separated from you.”

Decesare is also concerned about the mass volume at which students are consuming content from the media.

“I’m amazed, I just look over my daughter’s shoulder and she’s just looking at all these pictures and she’s just scanning through these things and she’s just consuming all of this stuff,” Decesare said. “And your brains are still being formed and you’re getting all of this mass of stuff and it can be really dangerous. You don’t realize that you’re taking it in.”

Social media often portrays the best of someone’s life. The absorption of these false images could negatively affect someone with predisposing risk factors and contribute to their suicidal ideations, or suicidal thoughts.

“That’s what people post, how happy they are and how great they are,” Decesare said. “Social media seems to highlight that ‘everybody else seems to be happy but me.’”

Haddon does not have this negative reaction to social media posts.

“I always get happier when I see somebody having a better day than me,” Haddon said.

Another important factor in teen suicide is the effect of pop culture.

In March of 2017, the drama series 13 Reasons Why was released to mixed reactions.

The show discusses many controversial subjects, all leading to the precipice of the story, the inevitable suicide of the main character.

13 Reasons Why is often criticized by mental health professionals for its gruesome portrayal of suicide and the horrific romanticizing of the act. However, the show also provided a way to reveal the secretiveness of teen life.

“They did a really great job of showing how secretive, adolescent relationships can be,” Geissler said, “of portraying how the adults aren’t privy to what’s really going on.”

Given the secrecy of those relationships, adults, teachers, and mental health professionals rely on communication.

Reports from friends of at-risk students seem to be on the rise, whereas there has been a decrease in at-risk students reporting their own suicidal ideations.

“Over half of students, from our last data poll, that have been feeling that suicidal ideation, didn’t tell anybody,” Russell said, “which is really scary.”

Resources such as the Care Line are ways that phones are helping to keep students connected and supported, as well as increasing administrative awareness.

The Care Line is a phone number and email address open 24/7 to students, parents, and school staff that addresses safety issues, threatening circumstances, and dangerous situations.

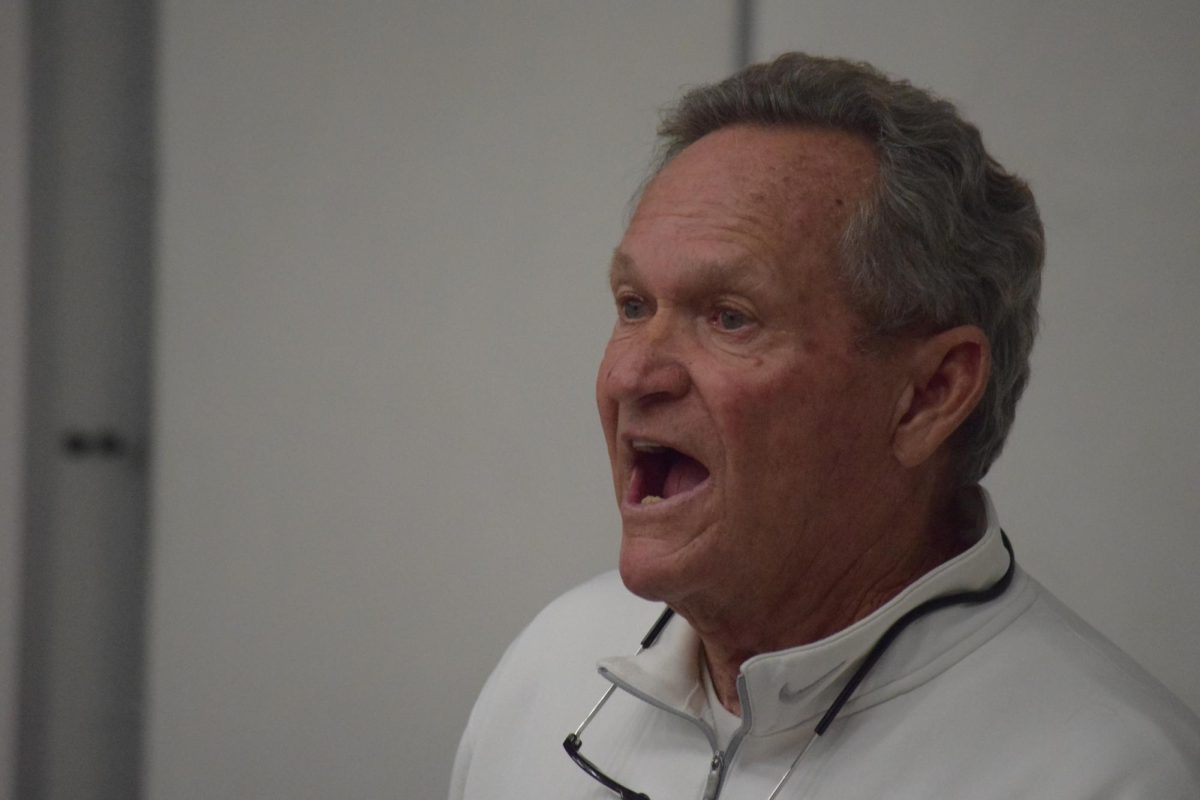

“There are some positives about this social media stuff because we do get Care Line calls about people that are worried about their friends,” Dean Tom Doherty said. “Kids reaching out and using the Care Line is a huge benefit to allow us as professionals to help kids.”

“It’s such an important piece of high school for kids to be aware and call that Care Line if they have any issues,” Doherty said.