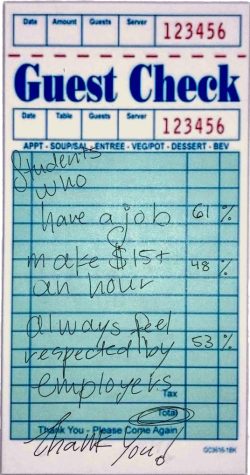

As teens across America go to work every day, the youth population is taking the job market by storm. It can be challenging to balance academic, social, and professional lives, but about 61.7% of students at Creek manage it every day, according to an October poll.

Nationally, that number is similar. According to the Employment and Unemployment Among Youth Summary, as of July 2022, around 60.4% of youth participated in the labor workforce.

For many students, work is a necessity, and has been viewed as a burden to students that feel like they’re not getting the necessary payoff from such a demanding part of their lives.

“I feel like I’m working all the time and barely get time to do schoolwork or hang out with people,” senior Alexey Aspen said.

In 2021, Aspen worked as a host at Longhorn Steakhouse and said approximately 90% of his fellow hosts were teenagers like him – all finding that the line between earning some extra pocket cash and healthy time management is growing thinner.

Senior Ellie Morris agreed that most of her coworkers were teenagers. She spent most of her time in 2021 working at Crumbl Cookies and earned an hourly wage of $9.30, despite the minimum wage at the time being $12.32.

A typical work week for Aspen was around three days a week, with around four to five hours a day, depending on what the weekend looks like.

Schedules like this can be difficult to balance for students with extensive sports, extracurricular, or academic commitments.

For senior Maggie Lee, this is why work only happens in the summer. She’s a member of the marching band, which takes up much of her time during the first semester of the school year and makes managing her time almost impossible, even without a job. “In a competition week, I’m doing band for probably more than 20 hours that week, you know, so it’s just a lot,” Lee said. “Marching band is the equivalent of a part time job.”

Lee makes up the difference between what money she spends and what money she’s unable to make during the school year by taking high-paying jobs during the summer. At the Renaissance Fair, where she works weekends, she makes around $500 a week, she said. The income is from minimum wage plus pooled tips. She says visitors to the fair tip well. “It’s not a teenager’s job. This is not the amount of money a teenager typically makes,” she said.

On Renaissance Fair weekends during the summer, Lee works 12 hours every day. Working long hours, especially back-to-back or immediately after a school day, can be ungratifying and exhausting. It’s not easy for teens to dedicate so much time to being socially and physically active behind a counter or in a kitchen.

“It takes a lot off of me physically, because you can’t even sit down the whole time,” Morris said.

This toll only worsens with the mistreatment of teenage workers by both fellow employees and customers. It can be easy for teens to be taken advantage of in the workplace, simply because they aren’t used to speaking up for themselves.

“Teenagers are seen to be dumb and inexperienced,” senior Mia Andre, a server and cashier at Tocabe, said. “Teenagers are often forced to work harder and longer hours to ‘prove themselves’ to their older co-workers.”

Healy, who now works as a kids’ gymnastics coach, sometimes feels disrespected by older coworkers. “They are all in their 30s, and I feel like they think they know better than I do and that I don’t have the responsibility to run a gymnastics class or deal with parents on my own,” she said.

Adams said that similar problems can come from teenagers not knowing how to stick up for themselves. “I think that they [teenagers] could [be disrespected] if they aren’t ready to say no to something that they can’t do, or be able to stand up for themselves towards rude customers,” Adams said.

Lee agrees on the need for teenage advocacy. “In my first year at the Renaissance Fair, I didn’t get all of my breaks or anything like that,” she said. “But then this last year, I learned how to advocate for myself more, and be like, ‘I just need to sit down,’ and then I would.”

When teenagers don’t speak up for themselves, they are put in undesired shifts and misused by their bosses. “There have been several instances where schedules have been changed last minute for me, or employers assume I can come in during non-schools hours when they’re short staffed, just because I’m not in school,” junior Gabby Clark said over text interview. Clark works as a cashier at Einstein’s, making $16 an hour plus tips.

Once Clark gets to her shift, problems can arise between herself and customers. “There have been many times where customers have blatantly been disrespectful but for the most part, the average customer is very respectful and considerate,” she said.

For junior Owen Adams, a shift manager at Snarf’s Sandwiches, conflict occasionally occur between customer and worker. “Whenever there’s a small mistake in the sandwich, I have to talk to the customer reassuring them that we’ll fix it if they can wait an extra two minutes,” he said.

These problems of disrespect are felt by Creek students. In an October USJ poll of 35.5% of 110 respondents said they sometimes feel respected by customer.

Said issues of wait times and wrong orders can become worse if the person working is a teenage girl or presents as one.

Senior Catherine Healy’s past hostess job at Earl’s made her feel uneasy. “As a host, I got hit on and talked to by old men more often than not, and to them it was an okay thing, but as a 16 year old girl it’s uncomfortable,” Healy said. “They didn’t speak like that to my male coworkers and they turned to them when they needed something instead of the host who was the one with the information.”

Although not as blatantly obvious, Lee also felt some of that prejudice when getting hired for her Renaissance job. “I think a reason I got hired was because I was a girl and they wanted a good storefront,” she said. “It’s like they wanted that image.”

Clark reflects the same feelings of misogyny. “There have been times when managers/older coworkers would treat male coworkers, with almost the exact same age and experience as me, way different. They will treat them as if they are way more mature whereas they tend to be more bossy toward women workers,” she said.

Andre agrees that prejudices against girls in the workplace are not uncommon.

“I think that girls especially aren’t taken as seriously in terms of career,” Andre said. “At my old job, girls would constantly get in trouble for ‘chatting too often’ or ‘being distracted,’ when boys would do the same with no punishment.”

Regardless of the cons of working, many still say that their jobs are a positive piece of their lives. In the same October USJ poll, 87.3% of the 110 respondents said that they enjoyed their job often or always. 81.6% said that they feel respected by employers.

“I feel absolutely respected by my employers,” Andre said. “I feel like my voice and contributions to the restaurant are more recognized and appreciated because it’s a small business. My employees have also always been accommodating to me when I’ve needed it the most.”

Teens in the workforce often need a job to make necessary money. Some are saving for college or life out of the parents’ houses. Others are funding outings with friends or other activities.

“I bought my car after I worked at the fair,” Lee said. While Lee’s parents paid for part of the car, Lee still had to make up the difference on her own – a couple thousand dollars out of her own pocket. She also said that having money from summer jobs means she can spend during the school year without picking up another job.

Adams agreed. He pays for his own gas, and likes having money from a job to spend on both wants and needs.

Many student workers don’t face financial difficulties in their families, but still want to gain independence from their parents. Some, like Andre, say that being able to support themselves in part leads to more confidence in their freedom.

“If I really needed them to, my parents would help me pay for things, but it feels nice to be able to do things for myself. I’m also planning on investing some of the money I earn,” she said.

Clark also enjoys her financial freedom, and spends her paychecks on going out, buying clothes, and coffee. “I honestly just really like having some extra cash and having a job allows me to have that,” she said.

Teens can gain experience working a low wage job, building up skills that are appreciated by employers and giving them a valuable head start. By employing teens, managers have lower wage workers and can staff to higher levels as students build up their seniority in the workplace.

Healy expressed the importance of teens learning to be “self-sufficient” before leaving home.

“At a certain age, you will be on your own,” she said. “So I think it’s nice to be able to sort of get a head start with the responsibilities before you are fully out in the world with no comfort of your home.”

But the actual experiences of the job can be a plus for some students, too.

“There was one day when a kid in my class…handed me a letter at the beginning of class that said that I was her favorite coach,” Healy said. “Knowing I was actually making an impact on these kids’ lives is just so exciting and motivating to hear because it makes me want to continue teaching.”

For Clark, the enjoyable parts of her job are in the lulls in between rushes. “Whenever it’s not too busy and not too slow is when I’m my happiest there,” she said.

Working also gives some teenagers the opportunity to meet people they might never cross paths with otherwise. Lee recalls bonding with coworkers, some much older than her, during breaks.

“Me and my co workers did the tortilla challenge in the back area, and somebody bought tortillas and then we slapped each other with tortillas and that was a lot of fun,” Lee said.

Andre described similar bonding experiences with coworkers, even when she was brand new to the job.

“All of our salsas are made in house, so the chefs make pepper paste to make the salsas spicy,” she said. “When I first started working there, they told me I should try a scoop on a chip as part of my ‘initiation,’” she said. “It was probably the spiciest thing I’ve eaten in my entire life, but it was a really good bonding experience, because my co-workers did it with me.”

The commonality and community formed with coworkers is often what keeps teenagers going in such a stressful and time demanding industry. And without it, the job itself can become unbearable. “I used to work at a good kiosk in the mall. I was constantly being talked about behind my back, and it seemed like my managers hated me. I never felt like a valued member of the team, no matter how much work I put in,” Andre said.