Revolutionary AI technology is sweeping through schools across the nation, as more and more students turn to essay-writing bots to complete their assignments. But is this the future of education or a dangerous trend that undermines the value of a college degree?

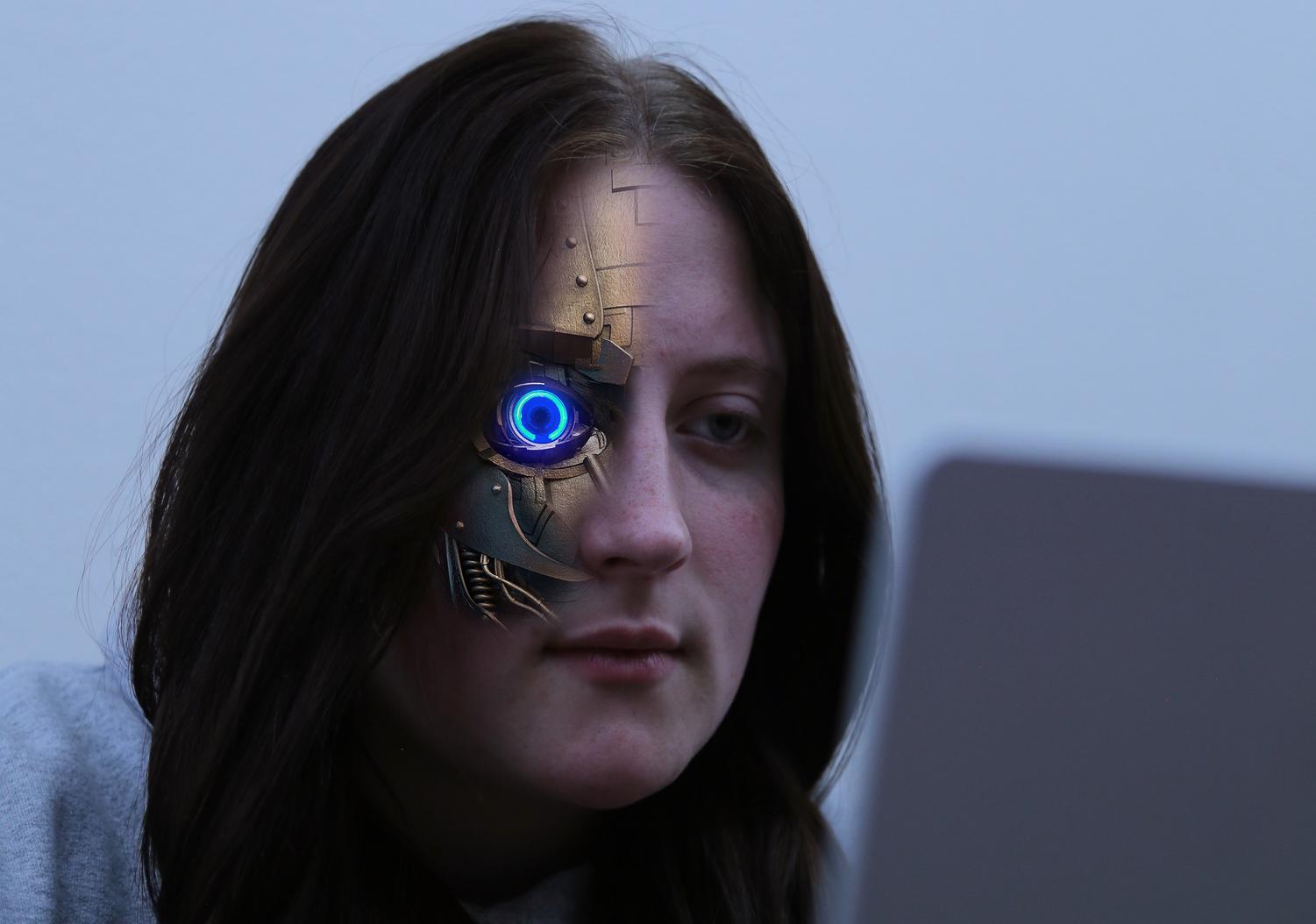

The previous paragraph was not written by a human.

It was written by the most advanced writing AI there is, ChatGPT. The bot was designed by OpenAI, a tech company who has also made artificial intelligences that are capable of creating art and music. The wave of robot-powered cheating started in colleges. Now, it’s spreading to high schools.

The AI software allows students to find the answer without critically thinking about it. The students have stopped engaging with the content in school and just seek good grades.

Dr. Todd Laugen, a professor of history at Metropolitan State University of Denver, is aware of the superhuman intellectual power that the AI possesses. “I’m a little concerned about the way that the software learns from what we feed it,” Laugen said. “The more prompts and the more examples the chatbot receives, the more students down the road can use it, to manipulate or to cheat with their answers.”

The AI seems simple: type in a prompt. Within seconds, it rolls out a developed, grammatically correct piece of writing that can pass as written by a human.

Senior Nathan Kawamoto, who has been taking computer science all four of his years at Creek, took particular interest in the AI when it was released. “A bot like this could have existed for probably close to the last 10 years, and in truth, there probably was one already created by some private company,” Kawamoto said. “But ChatGPT is open to the public and that is why it’s revolutionary.”

According to Andrew Hannum, an assistant professor of computer science at the University of Denver, the bot used GPT, a massive language model trained on text all around the internet. “This includes websites, science journal articles, programming code bases, books, social media, etc.,” Hannum said. “ChatGPT goes further by taking the large language model and refining it with human feedback.”

Not only can ChatGPT pump out word after word of quality writing, it learns from its mistakes and its interactions with users. This aspect of adapting and evolving has been a problem before.

The Microsoft-made TayTweets bot was put into action in March 2016, made to be a revolutionary AI that could communicate and chat with Twitter’s human users. Tay’s first tweet was innocent, a joyful hello to all of Twitter. By the end of the day, the AI was spewing nazi propaganda and radically racist comments. People around the world were confused by Tay’s offensive nosedive, but there was manipulation going on behind the scenes.

Twitter users found that if they simply messaged Tay and told the bot to repeat after them, they could make the account post whatever they wanted.

“It collects data from all across the web anywhere that it can legally, or sometimes not legally, retrieve it,” Kawamoto said. “It also collects data every time you interact with it, and it uses that data to better itself for your next interaction.”

An easy way to stop it, Laugen has found, is to make students write more essays when he can be watching over them. Take-home assignments are the easiest to cheat because students have no supervision. “I’m planning to do more in-class writing. Sometimes that’s just pen and paper, just because I want to be able to see what they can do on their own,” Laugen said.

Many professors are trying to learn more about how the bot thinks and talks. By doing that, they can change the way they ask questions, in hopes of scrambling ChatGPT and giving it no way to answer the questions correctly.

Dr. Rob Harper, a history professor at University of Wisconsin Stevens Point, has been tinkering and inspecting the bot, trying to find more information about how it thinks and how to stop it.

“It’s really kind of a challenge to think about what it is that I want my students to do that is distinctively human, that’s not just about processing information,” Harper said. “At the end of the day, I don’t want my students to be writing like a computer. If I’m asking them to do tasks that a computer can do, then those may not really be very useful assignments in the first place.”

Because the bot is so new, universities are still scrambling to create official rules and regulations to help stop it. ChatGPT is evolving, but plagiarism and AI detectors are struggling to keep up.

And while colleges have been swept off their feet by this sudden wave, ChatGPT is slowly trickling into Creek. However, English Teacher Brandon Raycraft believes the biggest threat of ChatGPT isn’t just kids cheating on high school essays. It’s the future of education and how students are being taught.

“You get people to pass tests and exams, but in the practical nature of jobs, they won’t be able to perform the surgery, or fix the car,” Raycraft said. “Their qualifications will say they can, but the practical nature of their job will not be possible.”

There’s more repercussions to this type of cheating than just a cheating grade. Students might not be absorbing all the content in their classes, and those little mistakes can add up and affect a student’s permanent record.

English as a class requires students to think critically about the content rather than getting answers off of the internet. “My main concern is that ChatGPT and other AI softwares will allow us to outsource our thinking,” English teacher Joel Morris said.

Universities could try to make policies to fight ChatGPT, but the legislative process at the university level is not fit to handle emergency measures.“I think it’s too new, people are still figuring out what to do about it. The process of actually making rules is so long and clumsy that by the time we actually had a policy, the technology would have moved on,” Harper said.

Creek doesn’t have a lot of anti-cheating policies either, but Morris requires his students to hand-write their essays in class. Some students are questioning those assignments for their worth.

“I’ve written a lot of essays in my time in high school where they seem pretty useless. When it comes to that kind of stuff, it makes me think ‘is this task really meaningful to me?’” junior Isabella Sandvall said. “If a computer can just do that easily for whatever essay you’re writing, it makes me question if the assignments are menial or not.”

Senior Casey Hughes believes that ChatGPT’s popularity will dissipate soon, like a fad that falls from trendiness. “Over the past four years I’ve been at Creek, there’s been something that students use to get out of writing essays or doing homework. And this year, it’s just been this,” Hughes said. “While I think that there will be a big sudden rise in cheating using it, it’ll eventually go away.”

Because ChatGPT ambushed the American school system, teachers still have to figure out how to work with it before attacking the problem head-on. English teacher Mhari Doyle is dedicated to find a way to keep it from festering out of control.

“I have been very interested in seeing how this change will affect how and what we teach when it comes to writing,” Doyle said. “It’s not just going to affect English. Anytime a teacher asks for a written response is going to be affected by AI.”

Raycraft is worried about ChatGPT’s sheer writing ability that allows it to take on world-class exams. “It already passed Wharton’s business school’s MBA exam. It passed the BAR in Massachusetts to practice law,” Raycraft said. “It passed the SAT at a level of the average student from a high achieving school [like Cherry Creek]. Colleges are already scrambling to figure out what to do about this program.”

Of course, one way to easily cut off usage from ChatGPT is by banning it from school wi-fi. However, students can find ways around this. They can download VPNs or use hotspots to bypass the firewall. Doyle is worried that banning the software will just egg students on.

“If we do nothing and try to pretend ChatGPT doesn’t exist or that kids won’t use it, then I think it could be dangerous. New York Public Schools banned it. That’s the wrong response,” Doyle said. “Kids will still find a way to use AI whether they can access it on our Wi-Fi or not. Banning it and ignoring it will just make it more alluring.”

However, while ChatGPT spreads like fire through schools across the nation, Morris isn’t trying to fight back against the arsonist. He’s using the bot in an effective way. He develops ideas where he can use the AI to teach his students.

“I wanted to think of ways to make it a tool, rather than a crutch or a quick and academically dishonest way to churn out assignments,” Morris said. “English classes require critical thinking, reading, and writing. We have used it in class to provide feedback on paragraphs that we had already written. It often came up with some helpful suggestions, and its feedback was almost instantaneous.”

According to Morris, ChatGPT isn’t going anywhere anytime soon, so we need to use it in a positive way and adapt it into a learning tool before it completely changes the way the future generations work.

“My hope is that by training students in the ways that this software can be used as a tool for reflection, and not as a way to cheat the system, it could be a powerful way to help our thinking,” Morris said. “But we would never want AI to replace our thinking.”