Every student at Creek has seen it, or at least heard it. People tipsy at a football game, discussing where to pregame prom, or who’s going to have alcohol at their party for Halloween. But what happens when drinking gets dangerous? What happens when students drive under the influence?

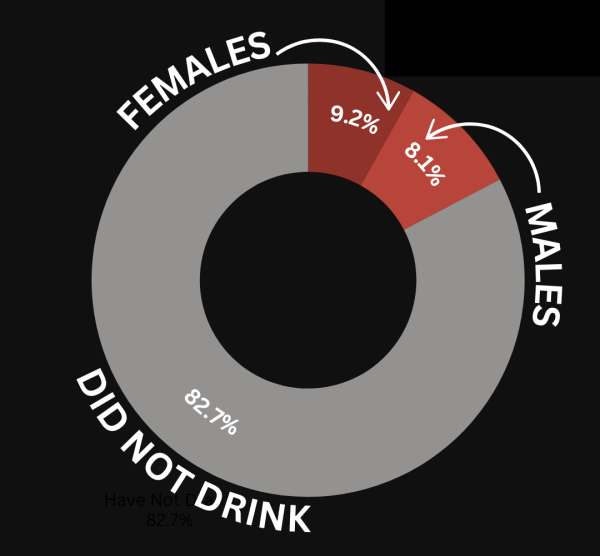

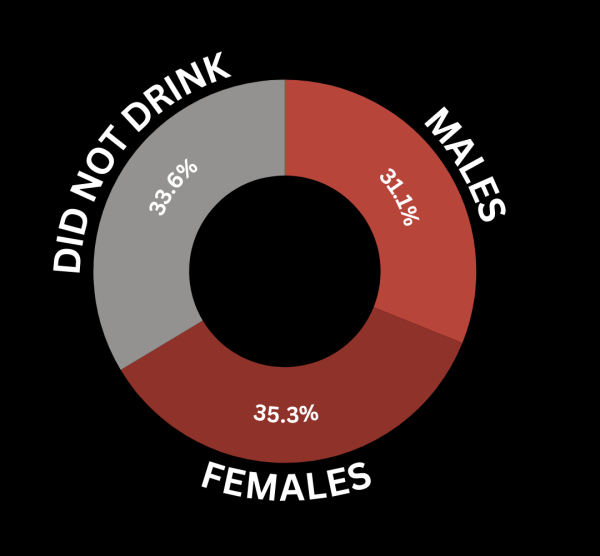

In 2023, 5.6 million youth ages 12 to 20 reported drinking alcohol beyond “just a few sips” in the past month, according to the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Colorado is ranked high in its amount of teenage alcohol consumption, with about 8.4 percent of teens reporting alcohol consumption. Colorado has some of the highest drinking rates in the country, behind states like Montana, Iowa, and Wisconsin, which had about ten percent of teens reporting drinking.

When students drink, the effects often spiral into every aspect of their life; academics, family and social life, their mental health, and even their general safety. Because of this, schools take the issue extremely seriously, and implement policies like education classes, informational handouts for parents, preventative policies, and substance abuse programs.

Creek follows procedures set by the district that deal with how to handle a student who is in possession or

under the influence of alcohol. But before any administrative punishment is involved, the school does tries to explain the effects of alcohol to students. Health classes detail how alcohol can change a developing mind, and substance use counselors are available to talk with students about any issues they have.

Health teacher Allison McKean believes that students use alcohol to cope, and hopes to use her class as a way to educate students about its’ true effects.

“Life is so beautiful with a clear mind. We all go through traumas in life, the important thing is to grow and heal so that we do not turn to drugs and alcohol as ways to cope,” she said. “All alcohol does is numb the pain.”

While health classes are more preliminary, Creek’s substance use prevention specialist Sarah White often interacts with students who have drank, and are struggling with their interactions with substances like alcohol.

“We talk a lot about what else is going on in their life,” Substance abuse counselor Sarah White said. “It’s not just drugs and alcohol, but everything’s connected, and everything impacts us.”

Affecting Students’ Mental Health

For years, studies have shown that being around intense alcohol consumption, or drinking alcohol yourself, has seriously negative effects.

And for students, the effects are even worse: cognitive issues, depression, and problems with self image.

According to Creek’s substance use prevention specialist Sarah White, the more students surround themselves with alcohol, the worse their mental health will be. And even though there are reasons that students do drink, it still isn’t healthy.

“It changes our brains,” White said. “The teenage brain is still developing, specifically those like the prefrontal cortex; so decision making, impulse control, organization, just all of those things [are impacted].”

White also wonders if some students drink because they struggle with their mental health; things like their self image, family or friend issues, and more. This is something that many organizations agree with: drinking is commonly used as a coping mechanism.

“The deeper aspects of anyone’s self worth, self assurance, self confidence, I wonder how much that’s at play,” White said.

As reported by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), students participate in drinking for many reasons beyond their mental health as well; sometimes they feel pressured to drink by their friends, or want to look ‘grown up.’

“As children mature, it is natural for them to assert their independence, seek new challenges, and engage in risky behavior,” the NIAAA study reported. “They may want to try alcohol but often do not fully recognize its effects on their health and behavior.”

Students who have reported drinking widely agree with this – drinking might be fun, but going ‘overboard’ is a different subject. “I have a strong opinion on it,” one anonymous junior said. “I think it’s bad. I think drinking and moderation is fine, but I actually can’t stand when someone’s like, ‘Let’s get hammered on a Tuesday night.'”

White’s job at Creek is to help students work through alcohol use, and to help them redefine how they view drinking. She never simply says “don’t drink,” but looks more into how students, after drinking, can help themselves and move forwards. However, she interacts with a very small amount of the student body.

“Not everyone knows I exist here,” she said. “Any student is able to come by at any time, and everything is confidential; I’m not going to call home and say ‘your student drank last week’ or anything.”

Q&A With Substance Abuse Counselor Sarah White

1) In your role as Substance Abuse Prevention Specialist, how do you help students?

“The relationship is the foundation. Every student is different, and our conversations will reflect that. I provide education on substances to help them make informed decisions. We discuss harm reduction, safety, goals and values, coping strategies and health habits, and more.”

2) Why is it important to talk to students about their experiences with alcohol and drugs?

“It’s important to talk about it so students have accurate information and can explore their decision making, values and goals.”

3) How does talking about these issues help students?

“Students have a safe, confidential (unless there is a safety concern) place to talk about their struggles, their substance use and their goals. My role is to support each student in whatever way I can to help them reach their goals. I want students to know I am in their corner and I support them no matter what.”

4) What’s some advice you’d give to any student?

“Wait until you are of legal age – research shows the earlier you start drinking, the more likely you are to become dependent or addicted. If you make the choice to drink: go slow and do not mix substances, have a safe ride home and be surrounded by people who are safe and looking out for you.”

School Policy

Currently, Creek aims to prevent students from using alcohol through the health classes that all students are required to take, which cover the effects of alcohol, as well as alternate coping mechanisms.

According to Principal Ryan Silva, these classes serve as a way to dissuade students from drinking because they explain the effects of alcohol on a teenager’s body.

These classes, Health and Health Hybrid, are required for all students in order to graduate. However, most students take these classes as a sophomore, even though there’s more pressure to drink as students become upperclassmen. Often, this means that students are being pressured to drink after they’ve taken these classes, and the knowledge has dissipated.

Because of this, Silva agreed that the health classes weren’t the school’s strongest area of alcohol policy, but also noted that the school rarely sees any issues with alcohol possession or driving under the influence.

“It’s probably not a big area of strength in terms of preventative [policy,]” he said. “We don’t have a huge number of drinking infractions. I don’t want to pretend like we don’t have them at all, but it’s not something that’s bigger for us.”

Even though the knowledge might wear off as students get older, health teacher Allison McKean believes that the health classes allow students to learn more.

“I believe that knowledge is power,” she said. “It is important to learn about the risks associated with alcohol and empower kids to want to make the right choices and say no.”

The classes use specific projects to guide students into learning more about alcohol, but also other methods of coping. “They do a project that showcases their ‘natural highs.’ Whether it be skateboarding or football and teaching them that drugs and/or alcohol can lower the natural dopamine produced from the things they love,” McKean said.

Beyond health classes, Creek also has policies that prevent students drinking at school activities, like sports games. As the athletics director, Jason Wilkins oversees a lot of the processes that help dissuade alcohol entering the school.

At any given sports game, there are security guards stationed at entrances to check students’ bags, and make sure nobody is taking backpacks into games. Beyond this, more security members are used for special events, like the homecoming football game.

“We have, obviously, police, security and deans at [the student] entrance and students are not allowed to take backpacks, drinks or food in,” Wilkins said. “So that does a lot of limiting of people trying to smuggle alcohol into games. And then, of course, we have security and people all over the stands.”

If a student is caught with alcohol, or is intoxicated, at an event, their dean or an available dean will pull the student out of the event, and then discuss the ‘next steps’ with the Greenwood Village Police. Often, a student will receive a punishment like an underage ticket for disorderly conduct citation from the police afterwards.

“Hopefully there’s not a lot of [drinking] going on, hopefully if students are choosing to partake in those kinds of things, that it’s at home, or they’re not driving,” Wilkins said. “Hopefully they’re not doing it anyway, because they’re not 21 so it’s not even legal.”

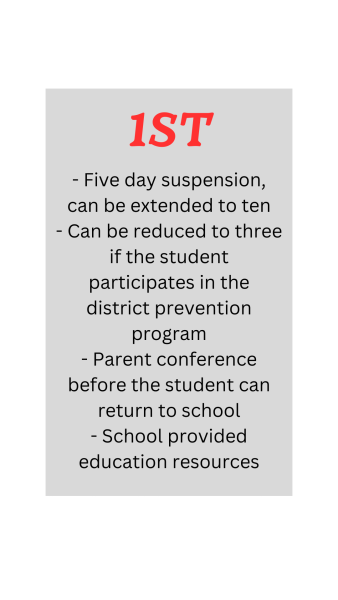

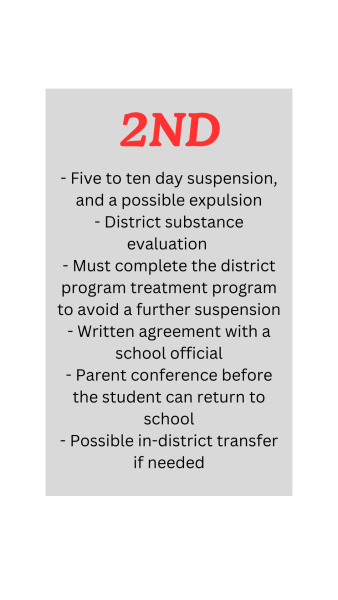

Admin Policy

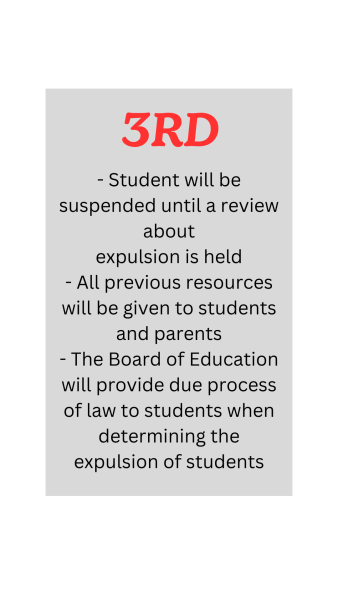

The district’s administrative policy for alcohol and drug offenses differs for each student by their amount of offenses. Overall, the district guide states that a violation is “for any student to use, posses, distribute, sell, procure, give or exchange or to be under the influence of alcohol,” and when their behavior can harm the welfare of others.