Underlying Impact

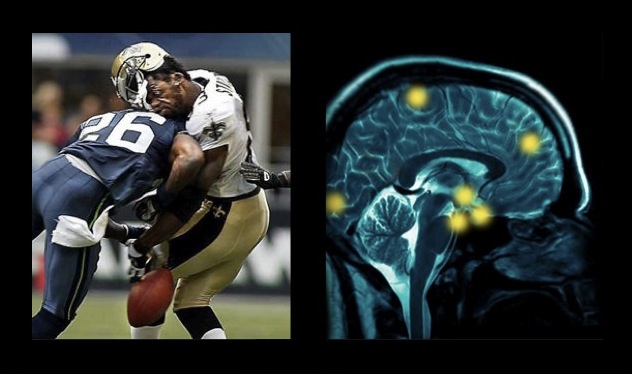

Analysis of Concussions in Football

December 10, 2015

In recent years, the publicity given to concussion research has both inspired people to help, as well as frightened people about the dangers of concussions and brain injuries.

Throughout the history of football, injuries have been commonplace. It makes sense. It is a rough game, and in order to play at a high level, a certain amount of toughness is required. The question to raise is this: when does being tough put certain aspects of a player’s health at too much of a risk, specifically the brain. The brain is a tricky organ because once nerve pathways are destroyed they cannot regenerate. Anytime a player is on the football field, he or she ends up being in danger the entire time spent on the field both in practice and in the games.

Up until recently, not much was known about concussions and how much impact they leave on those who have stopped playing the game. From the inception up until the mid-2000s, playing through headaches was commonplace. Not only was it expected to have a headache while playing, it was subtly implied by all coaches that said “If you don’t ring your bell at least once, you aren’t playing hard enough.” In truth, a headache during the game is a warning sign the body gives to make aware the fact that your brain is bleeding.

Even still, players try to be resilient by being quiet about their head trauma. According to ESPN.com, 57.7% of high school football players don’t report their concussions to coaches, in colleges only 0.03% are reported, and in the NFL, an entire third of concussions are left off of the injury report. This is an unfortunate fact of the game that needs to change for the health of those involved.

The magnitude of effect that multiple concussions can have was personified three years ago. On May 2, 2012, the former all-pro Hall of Fame linebacker Junior Seau was found dead in his San Diego home. The cause given was a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the chest. Upon further inspection, the authorities found a note in Seau’s handwriting, all it asked was to donate his brain to science. Neurologists discovered that Seau had endured extensive brain damage due to unreported concussions. Medically, Seau was given a postmortem diagnosis of CTE (Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy), which is a degenerative brain disease. In Seau’s case, he had a twenty-year career at the linebacker position, in which case he had contact made on every play. Players and coaches know of this to be true, yet it is not discussed openly between them.

In most cases, players will take “stingers” as badges of honor and won’t report it out of pride or fear. One of Seau’s former teammates, Gary Plummer, was also a linebacker and told the “LA Times”, “Any linebacker who doesn’t see stars at least five times a game isn’t doing their job.” Those close to Seau recall some of his behavior as being strange. Family members and former roommates remember that he had trouble sleeping for the entire time he played in the NFL. He was prescribed Ambien, but he could still not get a full night’s sleep even while taking his prescribed dosage. In hindsight, Junior’s body was being choked at the brain.

In a recent study done by CNN 87 of the 91 ex-NFL players who were tested had CTE due to trauma suffered in competition, this equates to 95% of the tested population, which is as staggering as the blows that cause the damage. CTE physiologically is the release of Tau protein that sits on top of the neural pathways and chokes the brain, shutting down the body. The NFL has committed a $30 million research grant to the National Institute of Health to better the understanding of a disease that, as of now, can only be diagnosed after death. In the seven years of research doctors can see that CTE shares a lot of the same symptoms as Alzheimer’s. In both cases, there are no symptoms present until decades after living with the disease. A lot of progress has been made in a short time, and with continued research and support, the questions about CTE will begin to dwindle. Currently, the patients studied have been self-selected. Neurologists hope to soon be able to test all of the players in the NFL as well as College and high school athletes.

The main thing hindering the progress of the CTE study is the amount of secrecy and dirty play involved in the athletic training field. Jim Pallotto Jr. played football from the age of seven all the way through five years of college where he competed in NCAA Division II Football at Western State Colorado University. During his career, he confirmed that he was able to hide injuries such as dislocated fingers, ankle and knee problems, and a few “stingers” (headaches). When specifically asked about hiding concussions, Jim stated, “Yes. The old concussion protocol was less than perfect.”

Jim’s response, as scary as it is, is warranted. The concussion test on the sidelines used until this year was based on balancing and whether or not the player sways a certain way. The problem with this type of testing is, once the players learned which direction signaled the trainer of a concussion they would make a conscious effort to sway the opposite. This means that a lower grade concussion could be hidden from those who aren’t looking hard enough.

In 2015, the NFL created a new sideline concussion protocol that incorporates electronic tests for observation of the following: cervical spine and bleeding in the brain, assessments of orientation, immediate and delayed recall, and, finally, concentration. The new test was developed by the head trainers and team physicians of the thirty-two NFL teams. The only obstacle for implementing this for high school and youth leagues is the fact that the test needs to be run on an internet capable-device such as an iPad, which costs more than most teams can afford. When asked if he thought the new protocol would help stop hiding concussions, Pallotto replied, “I hope so, since all of my boys play football. I think any progression that could be made toward determining and treating head injuries in all sports is a great thing. The great thing about the new test is that it is objective rather than subjective.”

Jim’s fatherly concern is shared across the country as the number of high school players has dropped by 21,353 since the NFL concussion study was released. For what is the nation’s most popular sport the discoveries made about the consequences of playing have certainly had an impact. This is not to say that football is struggling to get players to come out, but this is the lowest amount of high school players since the NFL merger with the AFL, The American Football League, in 1966.

Since 2011, the NFL has been in the courtroom enduring litigation for a player’s lawsuit for concussion compensation. The legal battle has a few leaders, including local football legend and Pro Football Hall-of-Famer Karl Mecklenburg. Mecklenburg was recently interviewed by USJ, and when asked whether or not the trainer or coach had ever hid an injury. “Yes, there were both doctors and trainers that wouldn’t tell a player the severity of their injury.” This would be the worst case scenario as a player, not knowing how bad an injury truly is multiplied the chance for an even worse injury.

Mecklenburg was known for his aggressive style of play and has been very vocal regarding head injuries stating, “I have had at least a dozen concussions, and have been knocked unconscious three times.” The NFL has come out and said that players with an aggressive style of play knew the risk they ran as far as injury is concerned, but with CTE being such a newly found disease, the NFL has agreed to pay former players, that show signs of: Multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s, or dementia up to 5 million dollars per family. Mecklenburg will be one of the players who will undergo the tests to show he is eligible for compensation. He explained, “My understanding is that we will have memory tests, scans, and balance tests that will be repeated if the player tests positive for any one of the possible diseases. This is not a way to collect money. This will support families as they help their loved one with a terrible disease.”

The main goal of everyone involved in football, CTE studies, and the NFL lawsuits have the same goals: help prevent brain trauma and its effects on the younger generation and to help those who are already affected and their families. Sometimes, the drama of the debates draws attention away from those who really need help. Hopefully, the problem will become as close to resolved as possible for the sake of the families and players suffering from brain trauma.

![Creek Unified, the program that promotes inclusion of those with disabilities, through team sports. “I like unified [because] I get to see my friends,” Debolt said. “And I like to play [with] all the boys.”](https://unionstreetjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/thumbnail_WrynsEditsFINAL-email-new-keep-final-copy1-600x436.jpg)